Icon adapted from work by Piotrek Chuchla on TheNounProject.

Critical Race Theory (or CRT for short) has become a lightning-rod issue in the past few years. Conservative pundits, politicians, and journalists continue to argue that CRT is liberal propaganda that reinforces racial essentialism and makes White kids feel ashamed about being White. Advocates for CRT assert that the theory has been misrepresented and warped into a boogeyman, a catch-all phrase for everything conservatives disagree with in terms of how Americans learn about race. In a phenomenon that has become all too commonplace in our modern media landscape, the definition of critical race theory has been subverted into a concept that conservative Whites can rally against in the name of free speech, unity, and traditional values. Yet what they are really doing is arguing for the maintenance of the status quo: An education system that maintains White supremacy while shutting out any voices that center minority perspectives or try to analyze social inequities.

This debate is the latest front in an ongoing fight by White conservatives to censor discussion of race and racism in classrooms (for an earlier example from over a decade ago, see this article on former Arizona governor Jan Brewer’s ban on ethnic studies courses in that state in 2010). To better understand the nature of the national discourse on CRT, we need to peel back the layers of the psychological mechanisms at play by answering the following questions:

Why are White people so upset about this?

Where do these reactions stem from?

What are some ways to teach the lessons of CRT without pissing people off?

To get to the bottom of these questions, let’s take a look at CRT and then unpack some concepts from social psychology that help shed light on White reactions to racism and White privilege.

What is Critical Race Theory?

At its core, CRT is an idea (stemming from legal scholarship) that racism is not just the result of individual attitudes or biases. It is structural and embedded within American social institutions, specifically the legal system, that people of all races interact with. Scholars of CRT – such as one of its originators, UCLA law professor Dr. Kimberlé Crenshaw – advocate for using a critical lens when studying the legal system that takes into account the very real history of racism in our country and how that history has influenced the law as it is put into practice today. There are many great articles out there explaining CRT and the insights it can provide into inequality in American society today.

Here’s John Oliver doing a nice explainer on CRT in his typical exasperated fashion:

Video source: Youtube courtesy of HBO.

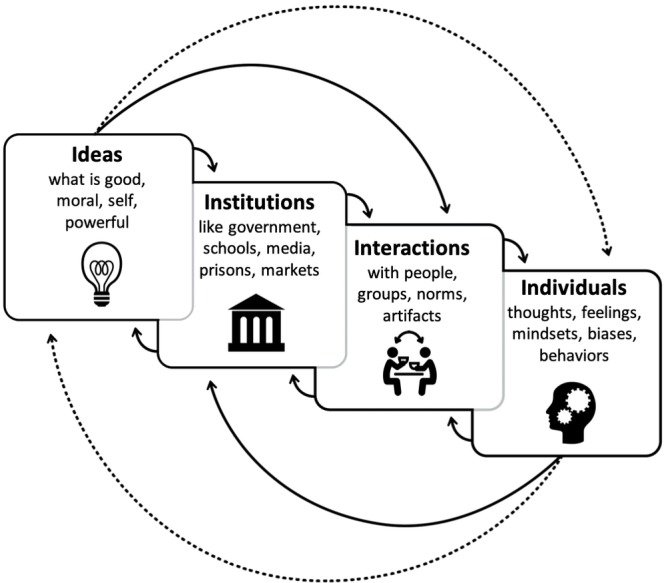

The conceptual framework of CRT can be mapped out using the theory of mutual constitution (or “the culture cycle”) in cultural psychology (Markus & Kitayama, 2010) – that we as individuals both shape and are shaped by cultural interactions, institutions and ideas:

The Culture Cycle. Image from Hamedani & Markus (2019).

CRT acknowledges that racism is not simply an individual feeling or behavior, but something that is shaped by the legacy of older, racist laws and rulings that still influence the legal system today. This maps onto the cycle of mutual constitution in the sense that White supremacist ideology (Ideas) influenced laws and legal scholars of the 18th and 19th centuries (Institutions) which in turn led to many rulings and laws that perpetuated racism (Interactions and social norms affecting individual attitudes and behavior). Individuals, in turn, bring their beliefs about race to interactions with others, shaping group norms and affecting cultural institutions they interface with. The “culture cycle” offers a helpful visualization of how ideas within a culture shape everything from laws to social norms about what is acceptable dinner table conversation to individual biases and behaviors.

It is also important to note that the forms in which structural racism manifests in institutions has changed over time. The Civil Rights Act of 1964 banned discrimination “on the basis of race, color, religion, sex, or national origin”. This resulted in a shift in how American institutions treated individuals on the basis of race. While “Jim Crow” laws were outlawed in the wake of this decision, ending the formal practice of racial segregation, de-facto segregation continued in other ways – such as public schools and transit infrastructure in White neighborhoods receiving more funding than those in predominantly Black neighborhoods (Zuk, 2015). This manifestation of segregation has had lasting negative impacts for Black children, including lower standardized test scores compared to White children (Garcia, 2020). Additionally, backlash by Whites in the 1950s and 1960s in response to the advancements of civil rights shows that institutional changes do not necessarily result in linear or all-encompassing social change (Richeson, 2020). In fact, the modern pushback by Whites against CRT shares a key characteristic of the White resistance to desegregation: Outrage at the notion that their worldview and value system, and therefore their actual and perceived sense of power, was being challenged. As social norms around race shift, so do the forms in which racism is expressed by individuals and maintained through institutions.

Applying the Critical Lens

CRT is a framework for understanding the impact of racism on laws and the legal system, but its critical approach can be applied to other social structures including the education system, finances, mental health supports, and urban planning (e.g., Kolivoski, et al., 2014). Psychological research on these topics have yielded fascinating results. For example, a recent study by Michael Kraus and colleagues (2019) found that Americans underestimate the wealth disparity between Black Americans and White Americans by around 80 percentage points. This misperception illustrates the need for a greater focus on how structural racism has important impacts on real-world consequences, such as accumulation of wealth. As Kraus notes in the paper:

“…any effort to increase awareness of racial economic disparities will need to be conducted with care, including offering important information about the role of societal racial discrimination and other structural factors in creating the racial wealth gap while refuting the likely default assumption that the gap is caused by poor individual-level personality characteristics or behavioral choices on the part of racial minorities”

(Kraus, et al., 2019, p. 16)

One last thing about CRT is that it is pretty advanced stuff! It is taught to law students and doctoral scholars, and sometimes advanced undergraduates. No third grader is reading legal analysis by scholars of CRT, regardless of what Fox news might be saying. So why is there a huge moral panic about CRT being taught in primary and secondary schools across the US? What these people are mad about is not CRT itself but rather what it represents – examining racial identity and the role it plays in perpetuating inequality in different social structures over time. The 1619 project, an activist movement focused on recentering American history education around the lasting impacts of slavery, has received backlash similar to CRT (critics even lump these two separate bodies of work together) (Hannah-Jones, 2021). For a deeper dive into White backlash against changing how history is taught, check out this excellent article on White American’s psychology toward past racial wrongdoing by Dr. Gerald Higginbotham.

People who are mad about CRT are angry in part because their narrative of American history is being challenged, which can lead to feelings of meritocratic and group-status threat. These feelings of threat trigger privilege defense mechanisms and backlash in the form of protests and anti-CRT laws. To better understand these mechanisms, let’s explore some psychological research on White reactions to information about racial privilege.

Psychological Underpinnings of Negative Reactions to Critical Race Theory

Some recent selections of news articles and videos demonstrate that outrage is one of the most common reactions to CRT among Whites. This maps on to a common defense mechanism that White people employ when confronted with information that triggers meritocratic threat, the feeling of threat when information is presented that shows that one’s achievements or status were obtained not due to one’s own effort but rather from one’s identity and background (e.g., skin color and intergenerational wealth). This threat is very uncomfortable and results in White people engaging in identity-protective thinking that reconciles this discomfort while preserving their positive sense of self. Eric Knowles and colleagues (2014) describe these defense mechanisms:

Figure from Knowles, et al. (2014).

While some White people may respond to information about their group status by focusing on dismantling the systems of privilege that lead to racial inequities, the negative responses of denying or distancing are much more common. One form that denial of privilege can take involves reframing the situation to make White people out as victims. Research by Danbold and colleagues (2022) describes this phenomenon of “digressive victimhood” when White people are accused of discrimination:

“A digressive victimhood response … involves the dominant group claiming victimhood on a dimension of victimhood distinct from the original charge of discrimination, thus shifting the conversation to a new topic (e.g., “The non-dominant group claims we are discriminating against them, but their accusations threaten our free speech”)”

(Danbold, et al., 2022)

Critics of CRT have used this technique extensively, claiming that CRT labels all White people as racist and that it limits free speech in the classroom (Israel, 2021). This line of thinking makes White people out to be the victims of CRT, effectively sparing themselves from the discomfort of thinking about racial privilege and reorienting the discourse about race in their favor.

Another mechanism at play in White reactions to CRT is that White people tend to have “zero-sum” beliefs about racial group hierarchies. Zero-sum thinking dictates that if one racial group gets more rights or opportunities, another group must be losing out (Norton & Summers, 2011). This kind of thinking leads some White people to make accusations of reverse-racism, following the zero-sum logic that if Black people are being discriminated against less then White people are being discriminated against more.

White people may also claim that there has been sufficient racial progress that society no longer needs policies focused on reducing racial inequities. This is a key belief of what Sears & Henry (2003) call symbolic racism. Symbolic racism is defined as the beliefs that:

“(a) Black people no longer face much prejudice or discrimination,

(b) Black peoples’ failure to progress results from their unwillingness to work hard enough,

(c) Black people are demanding too much too fast, and

(d) Black people have gotten more than they deserve”

(Sears & Henry, 2003)

Some form of these beliefs underlie many of the arguments against CRT because they also align with the conservative moral values of hard work, individualism, and delay of gratification. The interesting thing about symbolic racism is that many White people will openly acknowledge they hold these views but simultaneously deny that they are racist, a phenomenon known as racial egalitarianism. This is a key aspect of symbolic racism and how it shapes attitudes.

Let’s take a look at some of the efforts of critics of CRT to “rebrand” it:

Source: @realchrisrufo on Twitter

Here, CRT critic Christopher Rufo explains a tactic that conservative media outlets have used for a long time: reframing ideas that they don’t like (or “cultural insanities” as Rufo puts it) in a way that rallies conservative Whites against them. This tweet is a nice snapshot of one way that the denial defense mechanism of White privilege can take shape and lead to White backlash against racial progress. Conservative politicians and media figures have also lumped other movements for racial equity, such as the 1619 project, together under the umbrella of CRT to stoke feelings of threat and fear among White Americans (Hannah-Jones, 2021).

White anger towards CRT is partially due to a carefully-crafted, ongoing ideological war that conservatives have been waging to keep any examination of race/ethnicity out of the American education system. Conservative media has latched onto CRT and converted into a partisan talking point. One point that they like to reiterate is that CRT makes White people out as villians and being White as “evil”. This is another form of the denial defense mechanism in which White people claim victimhood, stating that they are being persecuted by the unveiling of structural racism.

Additionally, social norms about race and political correctness have shifted rapidly over the past decade, in large part due to Donald Trump’s election win and his use of mainstream media to advance his xenophobic views. Research by Chris Crandall and colleagues found that there was an increase in the acceptability of prejudice among all Americans towards social groups that Trump targeted (such as Muslims and immigrants) after the 2016 presidential election (Crandall, et al., 2018). In the framework of symbolic racism, this means that the facade of racial egalitarianism has been crumbling and giving way to outright prejudice. When social norms shift to make displays of prejudice more acceptable it is easier for White conservatives to garner more support for banning approaches like CRT that highlight racial inequality (and outrage and threaten White Americans).

Moreso than the shift of norms around egalitarianism, the White backlash against CRT has come as a response to greater numbers of White people becoming interested in antiracism after the killings of Black people by police in 2020. Many liberal White people took part in the large protests that took place after these killings and also were part of the reason that books like The New Jim Crow by Michelle Alexander and How to Be an Antiracist by Ibram X. Kendi became bestsellers. White liberals’ involvement with these protests further fueled claims of victimhood by conservative Whites as well as the pushback against this perceived threat to the racial hierarchy in the form of anti-CRT legislation and even the capitol insurrection (Jefferson & Ray, 2021).

Looking Ahead

The pushback by Whites against CRT is in itself evidence of the need for greater mainstream education about race in America. Research has shown that White people have increased anxiety (Richeson & Shelton, 2003) and tend to withdraw from conversations that focus on race (DiAngelo, 2011). Educational approaches that focus on the structural rather than individual factors that contribute to entrenched racism may alleviate some of this stress and increase awareness of racial inequities among White students.

People of color in America have a very different education than White people when it comes to race. They are often socialized about race, discrimination, and racism early on in their lives by family and peers (Simon, 2021). This is done out of necessity to prepare young children of color for the dangers of a White-centric society, a society that tends to misrepresent history to make White people out as the protagonists. For example, see this NPR article from 2015 about textbooks in Texas that described slaves in America as “workers” (Isensee, 2015).

The education system could benefit from educational approaches that take a page out of the CRT playbook. One reinterpretation of CRT could be: Instead of relying on one historical narrative about how American institutions were formed, incorporate multiple perspectives that take into account important power dynamics and social trends. However, this requires potentially uncomfortable conversations about Whiteness and the history of racism in America. The first step for White people to not be uncomfortable when talking about race is to have these conversations! And what better place to have them in a structured, intentional way than classrooms with teachers to help guide and moderate.

Teacher trainings are another effective tool to promote understanding of diversity in the classroom (Civtillo, et al., 2018). These trainings can increase teacher awareness of racial bias, highlight the importance of centering historically marginalized voices when discussing American history, and instruct teachers how to lead identity-safe discussions of potentially challenging topics such as race. Of course, these conversations can still backfire and lead to backlash, so it is important to implement evidence-based strategies to ensure everyone (regardless of their race/ethnicity) feels included. One such strategy is to “Teach about Structural Discrimination in Addition to Individual Forms of Discrimination” (Brannon, et al., 2018). This echoes the focus of CRT by focusing on how institutions reinforce discriminatory practices rather than individual discriminatory behavior. Other research has shown that completing a self-affirmation exercise (talking about another aspect of one’s identity that one feels good about) before talking about race can increase the willingness of White people to think about race in a structural way (Unzueta & Lowery, 2008).

While there is a large, media-fueled White backlash against critical race theory, psychology offers insights that can help White people move past anger and fear towards understanding and cooperation.

Takeaways

-

CRT is graduate-level legal theory and is not taught in primary or secondary schools! What most people are upset about when they say CRT is actually any educational approach that sheds light on the effects of structural racism

-

Negative reactions to CRT among Whites are largely motivated by meritocratic threat and group status threat defense mechanisms (Knowles, et al., 2014). These mechanisms are linked to a symbolically racist belief system predicated on preserving the status quo which maintains White supremacy (Sears & Henry, 2003).

-

Psychological research has shown that there are many real-world consequences of not teaching about structural racism, including misperceptions about racial wealth gaps (Kraus, et al., 2019).

-

Educators should incorporate a focus on social context and social structures when teaching about American history to help correct these misperceptions (See Brannon, et al., 2018)

Additional Reading:

Why are States Banning Critical Race Theory? – Rashawn Ray and Alexandra Gibbons:

How a Conservative Activist Invented the Conflict Over Critical Race Theory – Benjamin Wallace-Wells:

How White Victimhood Fuels Republican Politics – Neil Lewis:

White Backlash Is A Type Of Racial Reckoning, Too – Hakeem Jefferson and Victor Ray:

“Reparations?”: A case study of White Americans’ psychology toward past racial wrong-doing – Gerald Higginbotham:

References

Brannon, T. N., Carter, E. R., Murdock‐Perriera, L. A., & Higginbotham, G. D. (2018). From backlash to inclusion for all: Instituting diversity efforts to maximize benefits across group lines. Social issues and policy review, 12(1), 57-90. https://doi.org/10.1111/sipr.12040

Civitillo, S., Juang, L. P., & Schachner, M. K. (2018). Challenging beliefs about cultural diversity in education: A synthesis and critical review of trainings with pre-service teachers. Educational Research Review, 24, 67-83. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.edurev.2018.01.003

Crandall, C. S., Miller, J. M., & White, M. H. (2018). Changing norms following the 2016 US presidential election: The Trump effect on prejudice. Social Psychological and Personality Science, 9(2), 186-192. https://doi.org/10.1177/1948550617750735

Danbold, F., Onyeador, I. N., & Unzueta, M. M. (2022). Dominant groups support digressive victimhood claims to counter accusations of discrimination. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 98, [104233]. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jesp.2021.104233

DiAngelo, R. (2018). White fragility: Why it’s so hard for white people to talk about racism. Beacon Press. http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/1468017319868330

Garcia, E. (2020, February 12). Schools are still segregated, and black children are paying a price . Retrieved April 19, 2022, from https://www.epi.org/publication/schools-are-still-segregated-and-black-children-are-paying-a-price/

Hamedani, M. Y. G., & Markus, H. R. (2019). Understanding culture clashes and catalyzing change: A culture cycle approach. Frontiers in Psychology, 10, 700. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2019.00700

Hannah-Jones, N. (2021, June 14). Nikole Hannah-Jones Links Critical Race Theory Backlash To Spread Of Voter Suppression. MSNBC. Retrieved April 19, 2022, from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=i2PJNfOFNLk

Higginbotham, G. (2019, September 23). “Reparations?”: A case study of White Americans. Retrieved April 19, 2022, from https://www.psychologyinaction.org/psychology-in-action-1/2019/9/22/reparations-a-case-study-of-white-americans-psychology-toward-past-racial-wrong-doing

Jefferson, H., & Ray, V. (2021, January 6). White Backlash Is A Type Of Racial Reckoning, Too. Retrieved April 19, 2022, from https://fivethirtyeight.com/features/white-backlash-is-a-type-of-racial-reckoning-too/

Isensee, L. (2015, October 23). Why Calling Slaves ’Workers’ Is More Than An Editing Error. Retrieved April 19, 2022, from https://www.npr.org/sections/ed/2015/10/23/450826208/why-calling-slaves-workers-is-more-than-an-editing-error

Israel, J. Founders of ’Campus Free Speech Caucus’ want to ban teaching about racism on campus. Retrieved April 19, 2022, from https://americanindependent.com/gop-campus-free-speech-caucus-marsha-blackburn-tom-cotton-critical-race-theory-steve-daines-universities-racism-education/

Knowles, E. D., Lowery, B. S., Chow, R. M., & Unzueta, M. M. (2014). Deny, distance, or dismantle? How white Americans manage a privileged identity. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 9(6), 594-609. https://doi.org/10.1177/1745691614554658

Kolivoski, K. M., Weaver, A., & Constance-Huggins, M. (2014). Critical Race Theory: Opportunities for Application in Social Work Practice and Policy. Families in Society, 95(4), 269–276. https://doi.org/10.1606/1044-3894.2014.95.36

Kraus, M. W., Onyeador, I. N., Daumeyer, N. M., Rucker, J. M., & Richeson, J. A. (2019). The misperception of racial economic inequality. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 14(6), 899-921. https://doi.org/10.1177/1745691619863049

Markus, H. R., & Kitayama, S. (2010). Cultures and selves: A cycle of mutual constitution. Perspectives on psychological science, 5(4), 420-430. https://doi.org/10.1177/1745691610375557

Norton, M. I., & Sommers, S. R. (2011). Whites see racism as a zero-sum game that they are now losing. Perspectives on Psychological science, 6(3), 215-218. https://doi.org/10.1177/1745691611406922

Patterson, J. T., & Freehling, W. W. (2001). Brown v. Board of Education: A civil rights milestone and its troubled legacy. Oxford University Press.

Phillips, L. T., & Lowery, B. S. (2018). Herd invisibility: The psychology of racial privilege. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 27(3), 156-162. https://doi.org/10.1177%2F0963721417753600

Richeson, J. (Sep, 2020) The American Mythology of Racial Progress – The Atlantic. Retrieved April 19, 2022, from https://www.theatlantic.com/magazine/archive/2020/09/the-mythology-of-racial-progress/614173/

Richeson, J. A., & Shelton, J. N. (2003). When prejudice does not pay: Effects of interracial contact on executive function. Psychological science, 14(3), 287-290. https://doi.org/10.1111%2F1467-9280.03437

Sears, D. O., & Henry, P. J. (2003). The origins of symbolic racism. Journal of personality and social psychology, 85(2), 259. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.85.2.259

Sidanius, J., Van Laar, C., Levin, S., & Sinclair, S. (2003). Social hierarchy maintenance and assortment into social roles: A social dominance perspective. Group Processes & Intergroup Relations, 6(4), 333-352. https://doi.org/10.1177%2F13684302030064002

Simon, C. (2021). The Role of Race and Ethnicity in Parental Ethnic-Racial Socialization: A Scoping Review of Research. J Child Fam Stud, 30, 182–195. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10826-020-01854-7

Unzueta, M. M., Everly, B. A., & Gutiérrez, A. S. (2014). Social dominance orientation moderates reactions to black and white discrimination claimants. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 54, 81–88. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jesp.2014.04.005

Unzueta, M. M., & Lowery, B. S. (2008). Defining racism safely: The role of self-image maintenance on white Americans’ conceptions of racism. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 44(6), 1491-1497. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jesp.2008.07.011

Zuk, M., Bierbaum, A. H., Chapple, K., Gorska, K., & Loukaitou-Sideris, A. (2018). Gentrification, displacement, and the role of public investment. Journal of Planning Literature, 33(1), 31-44. https://doi.org/10.1177%2F0885412217716439

Other links:

https://www.theatlantic.com/photo/2014/05/1964-civil-rights-battles/100744/

https://www.foxnews.com/us/cupertino-elementary-students-race-oppressed

https://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2019/08/14/magazine/1619-america-slavery.html