Picture this: Two economists are going on a leisurely stroll together when they stumble upon a one-hundred-dollar bill lying on the sidewalk. The two promptly walk past it without giving it much attention. One of the economists turns and says, “Did we just pass a $100 bill on the ground?” The other economist replies, “Of course not. If there had been $100 on the ground, someone would’ve picked it up.”

If the humor of this old economics joke went over your head, let me give you some context. The discipline of economics is built on the assumption that all human beings are “rational agents” who make “rational decisions” with their money. Economic models of human behavior are based on something called rational choice theory (Nickersons, 2021) It is the idea that human beings are rational actors that will behave rationally when approached with a problem, especially in instances that involve monetary outcomes.

Remember that Benjamin on the ground? It can’t exist. No rational person would drop it on the ground. If someone did drop it, that would mean all of economics is completely baseless! As many students of cognitive psychology, behavioral economists, and other related fields have likely noticed, human beings are often quite irrational when it comes to making any decision, let alone monetary ones. To give more explanation, let’s go back to the birth of the field of economics and talk about it is related to and intertwined with the work of many psychologists.

Economics as a discipline goes back to the writings of Adam Smith in his treatise The Wealth of Nations in 1776. In the book, Smith observes that markets somehow naturally align with what is monetarily optimal. He dubbed this the “invisible hand” of the market, and the source of this phantom, he concluded, was the rational behavior people exhibit in regards to scarce resources. Following this idea of the human being as a rational decision-maker, he was able to construct economic models to predict the ebbs and flows of the economy with quite astonishing accuracy (Smith, 1776)

This seminal work of human behavior predated Freud by more than a century. In a way, economics was doing psychology before psychology became a science! Over the resulting centuries, economists came up with the concept of humans as utility maximizers (“utility” denoting the unit of desirability a kind of good has for individuals) (Aleskerov et al., 2007)

For example, if a person buys an orange over a banana, it means that the orange had more utility than the banana in that instant. Say for this same person, while an orange has more utility than a banana, an apple has more utility than an orange. Economics would predict that when presented with a choice of either an orange or banana, the person would pick the orange, and when presented with a choice of either an orange or an apple, they would pick the apple. Based on this line of reasoning, when the person is presented with the choice of a banana or an apple, they should pick the apple. This decision seems obvious and simple, but this idea of revealed preference was revolutionary at the time in its ability to quantify and understand human decision-making (Varian, 2006).

Unfortunately for economists, humans do not always follow this predictable, rational pattern of behavior. Thus, economics as a field eventually came to grips that their rational Homo economics was a myth. In reality, a person may go against all possible reasons and choose a banana over an apple.

In the 1960s, cognitive psychologists Daniel Kahneman and Amos Tversky started to lift the curtains on the rationale of human decision-making. From their insights, they sharpened a striking critique and stabbed it into the heart of economics. And from its carcass, they carved out the entirely new field of behavioral economics, where economics and psychology meet to inform one another (Hattwick, 1989).

The truth is that we are emotional beings with short attention spans. We go against our good instincts and make irrational decisions all the time. We even, on occasion, drop $100 bills on the ground. Throughout the decades of their research Kahneman and Tversky observed and described many cognitive biases and heuristics we use in place of rationality. They applied these concepts to many economic scenarios and found surprising results.

Much of these findings were highlighted in Kahneman’s book Thinking Fast and Slow published in 2011, which has become sort of a bible for cognitive psychologists and behavioral economists. To anyone interested in these areas of psychology, I highly recommend reading it. To lay out some critical findings of these early behavioral economists, let’s start with a bias called loss aversion (Kahneman & Tversky, 1979). It turns out that people dislike losing money much more than they enjoy receiving money. It is more painful to lose $100 than gain $100.

I will give a simpler example of what Kahneman and Tversky (1979) describes. Take this hypothetical

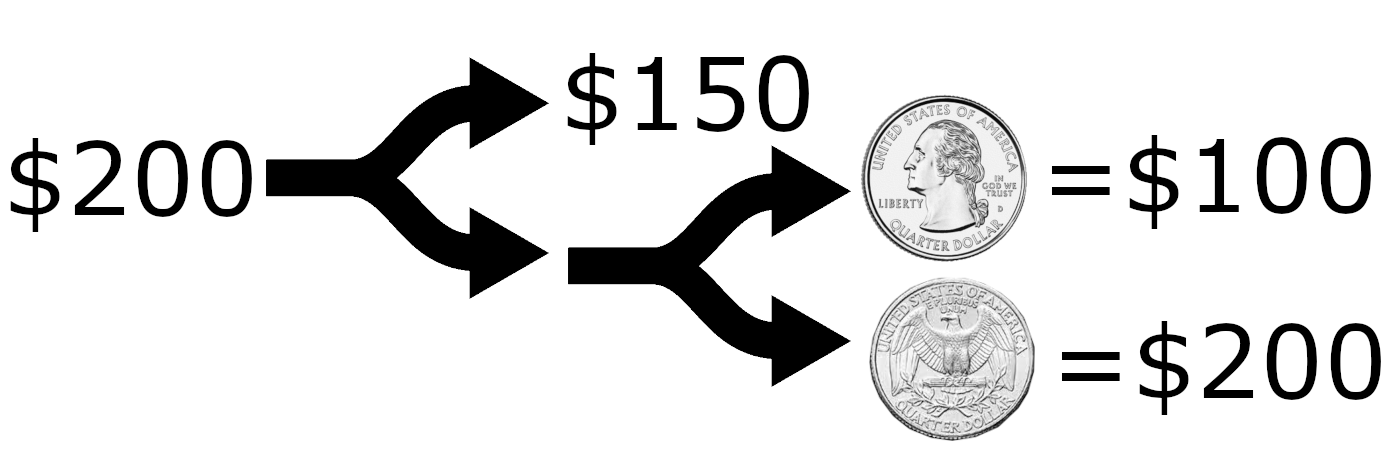

One day, you are approached by a mysterious figure who offers you a deal. Out of their pocket, they grab a $100 bill and hand it to you. They say, “You have two options, I will give you another $50 and you can walk away with a total of $150 in your wallet, or you can wager this $100 on a coin flip. If the coin comes up heads, I’ll double the amount you receive to $200. But if it comes up tails, I will take back the $100 and you will be left with nothing. What is your decision?”

Scenario 1

If you are like the average person that Kahneman and Tversky observed, you will choose to walk away with the $150. Now consider this second scenario that they tested on a different group. Parafrasing, it went like this:

The mysterious figure walks up to you and offers you a different deal. Out of their pocket, they grab $200 and hand it to you. This time, they say, “You have two options, you can walk away without betting any money, but I will take $50 of the $200 away from you, or you can make a coin flip wager. If it lands heads, I will take away $100. If it comes up tails, I won’t take anything away. Which decision will you make?”

Scenario 2

This time around, most people took the bet. But notice how in both situations, the safe deal comes out to be the one resulting in you ending up with $150. Kahneman and Tversky attributed people’s propensity to choose the wager in the second scenario to loss aversion. Losing $50 of $200 might not be practically different than receiving $150, but reframing the scenario has a noticeable effect on how we think and behave. Fearing the loss of the $50, people put themselves in a situation where they were more vulnerable to losing even more money.

Another bias that Kahneman and Tversky found is called anchoring (Tversky & Kahneman, 1974). People tend to hang on to the immediate information they are given and use that as their reference to decisions going forward. Psychologist Dan Ariely describes in his book (Ariely, 2010) how he conducted a survey to examine the effect that the anchoring effect had on participants’ choices in subscription type to The Economist magazine. He provided participants with three subscription options for the magazine: web, print, and both web and print. Each was listed at a different price. The percentage of participants that chose each subscription type was recorded.

Subscription Type Cost for a Year Percentage that Chose it

Web Only $59 16%

Print Only $125 0%

Web and Print $125 84%

Upon initial examination, one may wonder why The Economist would even offer print-only subscriptions if no one seems to want them. To examine the effect that including the print option had, Ariely conducted another survey without the print-only option and got interesting results.

Subscription Type Cost for a Year Percentage that Chose it

Web Only $59 68%

Web and Print $125 32%

The number of people who went with the web-only subscription increased dramatically! Essentially, the highly-priced print-only subscription acted as an anchor that made the identically priced web and print subscription look like a bargain that attracted more customers.

The classic sales technique of highballing (offering a very high price with the intention of making another high-priced item look more appealing) is explained by this anchoring effect. The moral of the story is to watch out for high-priced items as someone may be trying to dupe you out of your money by anchoring you.

To summarize, many of the initial ideas the field of economics produced about human behavior were based on a naive understanding of human cognition. Through the work of psychology and interdisciplinary communication, the field of economics has become better informed and expanded its understanding of human behavior and decision making. The story of behavioral economics should serve as motivation for psychologists to reach out to other disciplines to see what we all can learn from experts in related fields!

References

Aleskerov, F., Bouyssou, D., Monjardet, B. (2007). Utility Maximization, Choice, and Preference. 2nd ed. Springer.

Ariely, Dan. (2010). Predictably Irrational: The Hidden Forces That Shape Our Decisions, Revised and Expanded Edition. HarperCollins.

Hattwick, R., E. (1989). Behavioral economics: An overview. Journal of Business and Psychology. (4) 141–154 . https://doi.org/10.1007/BF01016437

Kahneman, D. & Tversky, A. (1979). “Prospect Theory: An Analysis of Decision under Risk”. Econometrica. 47 (4): 263–291. https://doi.org/10.2307/1914185

Nickerson, C. (2021). Rational Choice Theory. Simply Psychology. www.simplypsychology.org/rational-choice-theory.html

Smith, A. (1776). The Wealth of Nations.

Tversky, A., Kahneman, D. (1974). Judgment under Uncertainty: Heuristics and Biases. Science. 185 (4157): 1124–1131.

Varian, H., R. (2006). Revealed Preference. Samuelsonian Economics and the 21st Century. (Szenberg, M., Ramrattan, L., Aran, G., A.). Oxford University Press.