The horizontal-vertical (H-V) illusion is a well-documented perceptual illusion that refers to the tendency for people to overestimate the length of a vertical line relative to a horizontal line of equal length (Avery & Day, 1969; Künnapas, 1957). To demonstrate the horizontal-vertical illusion in a real-world environment and explore the impact of schemas and illusions on memory and perception, we asked UCLA students to estimate the dimensions and also sketch the dimensions of Pritzker Hall, the psychology building on campus (Murphy & Castel, 2021). Participants either responded while remembering the building (in a testing room with no windows) or while perceiving (standing in front of) Pritzker Hall to determine if the horizontal-vertical illusion results in similar systematic errors in both memory and perception.

Previous work has indicated that we often have poor memory for common objects like the letter “g,” the American flag, pennies, and the Apple logo (Blake & Castel, 2019; Blake, Nazarian, & Castel, 2015; Nickerson & Adams, 1979; Wong, Wadee, Ellenblum, & McCloskey, 2018). Similar to this previous work, we expected that participants would be inaccurate when recalling from memory but that they might also be inaccurate even when actively perceiving Pritzker Hall due to the influence of the horizontal-vertical illusion and the tall and narrow schema for buildings.

Theoretically, when Pritzker Hall is within participants’ sight, their sketches and estimates should be as accurate as or more accurate than when drawing and estimating from memory. However, despite Pritzker Hall’s cubic design (100 feet tall, 100 feet wide, and 100 feet deep), we expected participants to be inaccurate in both their memory and perception of the building. Specifically, we anticipated participants’ mental representation of a typical tall building in combination with the horizontal-vertical illusion to bias them to remember and perceive Pritzker Hall to be taller and thinner than its actual cubic dimensions. We also presented participants with a multiple-choice test of the outline of Pritzker Hall to determine if they not only produce incorrect sketches and estimates but also fail to recognize the correct shape, even when standing in front of the building.

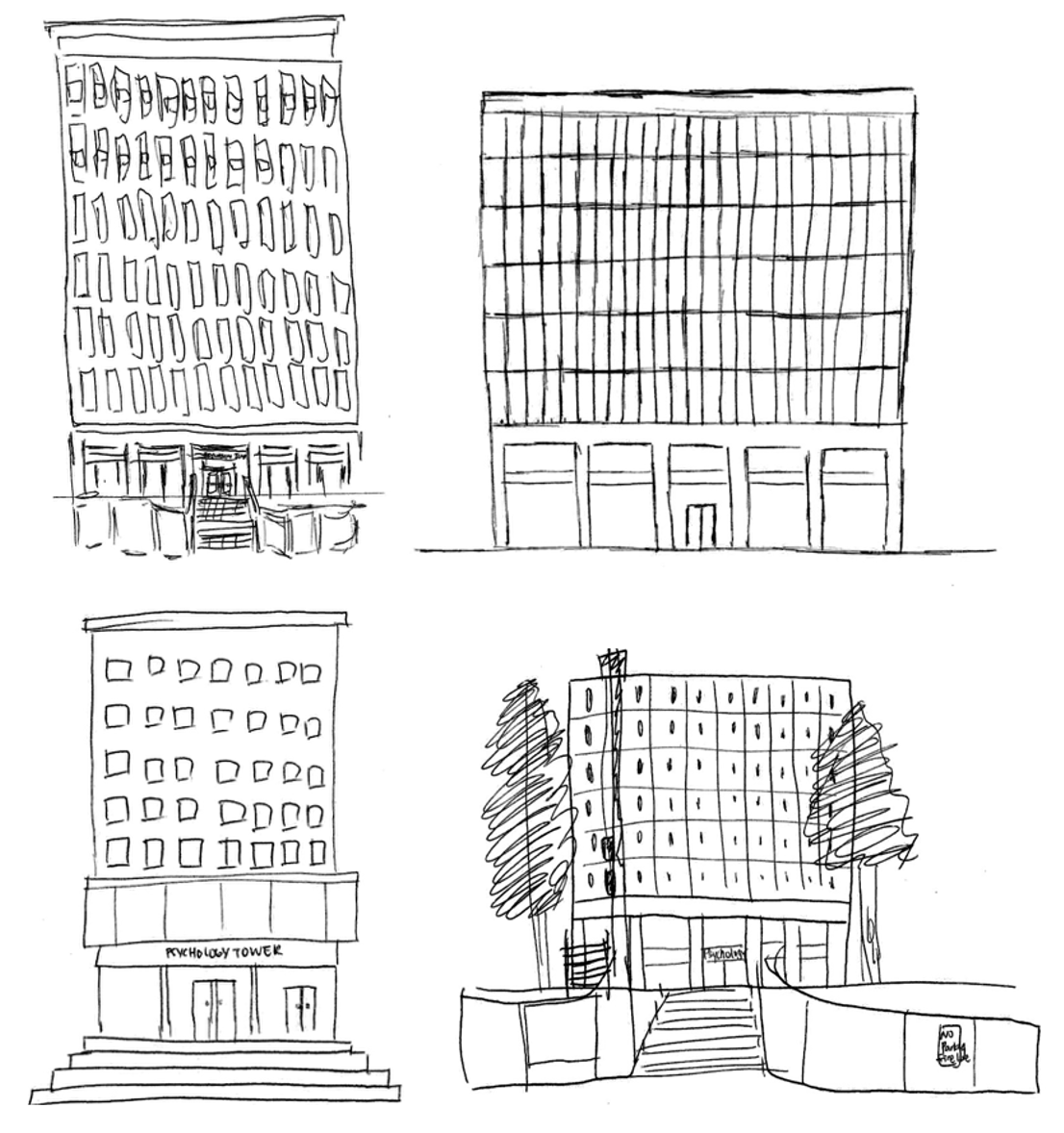

Despite having just entered Pritzker Hall or presently looking at it, results revealed systematic inaccuracy such that participants significantly overestimated the height to width ratio across experiments and conditions, indicating that both memory and perception can be influenced by schemas and the horizontal-vertical illusion (see Figure 1 for example sketches). Furthermore, on the recognition test, less than 4% of participants selected the shape with the correct height to width ratio; the vast majority of participants selected incorrect options that fit the schema of a tall and narrow building.

Holistically, participants’ estimates, sketches, and recognition selections conformed to a schema or illusion of a building being taller than it is wider, regardless of whether they were recalling from memory or looking at Pritzker Hall. Therefore, participants’ perceptual accuracy appears to be impacted by similar biases as memory, suggesting that schemas and the horizontal-vertical illusion affect memory and perception alike.

In sum, we demonstrated that perceptual illusions can bias both memory and perception, providing novel insight on how biases in perception can influence the reconstructive nature of memory, possibly through the reliance on schemas that are stored in long-term memory. Future work will benefit by examining misremembering and misperception of iconic buildings like the Gateway Arch in St. Louis, the Eiffel Tower, or the Empire State Building as people may frequently apply their knowledge and schemas to similar structures leading to memory and perceptual biases. As a result, despite frequent exposure and the apparent ease associated with recalling, recognizing, or drawing something right in front of you, memory and perception are not always as accurate as we may expect.

Figure 1. Examples of inaccurate drawings (left) and accurate drawings (right) by participants in Murphy and Castel (2021).

References

Avery, G. C., & Day, R. H. (1969). Basis of horizontal-vertical illusion. Journal of Experimental Psychology, 81, 376-380.

Blake, A. B., & Castel, A. D. (2019). Memory and availability-biased metacognitive illusions for flags of varying familiarity. Memory & Cognition, 47, 365-382.

Blake, A. B., Nazarian, M., & Castel, A. D. (2015). The Apple of the mind’s eye: Everyday attention, metamemory, and reconstructive memory for the Apple logo. Quarterly Journal of Experimental Psychology, 68, 858-865.

Künnapas, T. M. (1957). The horizontal-vertical illusion and the visual field. Journal of Experimental Psychology, 53, 405-407.

Murphy, D. H., & Castel, A. D. (2021). Tall towers: Schemas and illusions when perceiving and remembering a familiar building. Applied Cognitive Psychology, 1-11.

Nickerson, R. S., & Adams, M. J. (1979). Long-term memory for a common object. Cognitive Psychology, 11, 287-307.

Wong, K., Wadee, F., Ellenblum, G., & McCloskey, M. (2018). The devil’s in the g-tails: Deficient letter-shape knowledge and awareness despite massive visual experience. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Human Perception and Performance, 44, 1324-1335.