This article is authored by Katon Minhas and Lucy Cui and is part of the 2020 pre-graduate spotlight week.

We’ve all been there. Sitting in a lecture hall before a final exam that we may or may not be fully prepared for, frantically reviewing notes and hoping for a favorable curve. When the test starts, it generally goes one of two ways: 1) your nerves continue for a few minutes before you find a rhythm, realize you know way more than you thought, and proceed to fill in those bubbles like a champion, or 2) your nerves get worse, your hands start shaking, and you end up so distracted and unable to think that you end up with a score that you believe does not reflect your level of mastery.

If you find yourself relating more to Scenario 2, you’re not alone. Nearly 50% of college students frequently experience the psychological condition known as test anxiety(Kavakci et al., 2014). Test anxiety is a form of performance anxiety, the same sort of ‘pregame jitters’ experienced by an athlete before a big game. The term refers to the set of physical, cognitive, and emotional symptoms that may arise before, during, and after a test. While a certain amount of test-day nervousness is expected, test anxiety can severely lower a person’s cognitive capacity and make it harder to perform well. With such a large (and growing) portion of our student body affected, it is increasingly important for students to be aware of the underlying causes, symptoms, and solutions for dealing with test anxiety.

Causes

Test anxiety contributes to the downward trend in students’ overall mental health observed in recent years. It appears that the likelihood of test anxiety is much higher among people with high baseline anxiety levels (Duffy, 2019). It follows that as more and more students report higher levels of overall anxiety, the prevalence of test anxiety will continue to increase.

Of course, students with normal anxiety levels are not immune to feeling test-anxious. The Anxiety and Depression Association of America lists three main causes of test anxiety:

1) Fear of Failure– Students motivated by a fear of failure rather than a desire for success are less likely to challenge themselves academically and are therefore more likely to respond negatively to adverse situations (Piedmont, 1995). Avoiding challenges makes it harder to face challenging situations when they do arise, such as during a test.

2) Lack of Preparation– Feeling underprepared for a test is an overwhelming and extremely anxiety-inducing feeling that can be made worse by comparing your level of preparedness with your classmates.

3) Poor Test History– If you performed poorly on your midterm, it’s likely you’ll remember that feeling on the day of the final. Failing one test has a crippling effect on motivation and confidence when it comes time for the next one.

Symptoms

The symptoms of test anxiety are very similar to those of other forms of performance anxiety. Individuals may experience any number or set of symptoms, which generally fit into one of three categories:

Physical Symptoms

Physical symptoms are most likely to occur before and during the early portions of a test, but can disappear and return throughout. These include headaches, stomach aches or nausea, sweating, and shaking. If you find yourself experiencing any of these symptoms, it’s likely because your body has activated its fight-or-flight response. The fight-or-flight response is a very primitive defense system that becomes activated in response to a perceived immediate threat. When danger is detected, the sympathetic nervous system is activated, triggering the release of adrenaline and leading to increased heart rate, breathing, and several other involuntary responses. While the response is tremendously effective for preparing us to deal with physical threats, it doesn’t provide too much help with the psychological challenge of taking a test. Headaches and extreme discomfort can occur as a result of trying to tough-it-out and focus despite the very distracting bodily reaction. In addition, the alarming nature of these symptoms can actually have a loop effect and end up escalating tolerable test anxiety into a panic attack.

Cognitive Symptoms

The cognitive symptoms of test anxiety occur during test preparation and throughout the duration of the test and typically contributes the most to reduced test performance. Unlike the physical symptoms, some cognitive impairments brought on by test anxiety may not be noticeable by the person experiencing them. Most people are not consciously aware that their negative thoughts are decreasing their mental capacity.

The phrase “mental capacity” in this context refers to working memory capacity (WMC), our brain’s short-term information storage bin. Most people’s WMC is capable of holding 4-7 pieces of information at once. While we typically only use 1 or 2 of these spaces, cognitively challenging tasks are much more demanding and often require our full capacity. This is especially true for math-intensive tests as well as for reading comprehension, where every slot of your working memory capacity is needed to complete the task.

Several studies have demonstrated that moderate to severe test anxiety greatly decreases performance in working memory tasks due to a phenomenon known as threat-interference (Angelidis et al., 2019; Sarason and Irwin, 1984). By increasing attention to negative thoughts and external comparisons instead of focusing on the exam materials, test-takers increase their mental workload, leaving less WMC available for the test. This results in a significant test-taking advantage for people with naturally high WMC. A 2014 study by Owenset al.showed that moderate levels of anxiety during a math test significantly decreased performance in students with low or average WMC while improving the performance of students with high WMC. Because of the extra mental storage space, the high-WMC students were less affected by the same level of perceived anxiety and were even able to benefit from a slight boost in alertness.

Beyond just affecting working memory capacity, test anxiety has been shown to impair information processing and recall of information. Feeling anxiety during test preparation can lead to “poor conceptualization or organization of the content, limiting the ability to retrieve key information during the test” (Cassady and Johnson, 2001). You may not even realize you’ve organized information in memory poorly until you’re asked to recall it. You might find yourself endlessly racking your brain for a solution to a problem you thought would be simple. You might simply freeze up and stare at the problem for several minutes not knowing where to start. Both of these reactions are the result of your brain not knowing how to find the information it needs. Proper organization of information involves categorizing content based on meaningful rather than superficial relationships. For example, a student who only learns to associate multiplication with the × symbol will be stumped if given a multiplication word problem, even if they are proficient at the actual act of multiplying. Because the problem lies in not being able to access the information rather than not having the information, it is often difficult to diagnose the issue until it is too late.

Both of the above-mentioned cognitive impairments are also subject to a cyclical loop effect – a sort of self-fulfilling prophecy where the awareness of your cognitive limitations leads to even more anxiety, which leads to more impairments, and so on (Naveh-Benjamin, 1991). Depending on the severity of symptoms, this effect can range from a temporary disturbance to a complete debilitation.

Emotional Symptoms

The emotional symptoms of test anxiety can manifest at any time during the test-taking process and can even continue long after the test is over. Symptoms include feelings of helplessness, low self-esteem, and depression. Many emotional reactions to test-anxiety stem from a feeling excessive pressure to succeed. Negative emotions are typically experienced more strongly by people with maladaptive perfectionism, a trait characterized by unattainable goal-setting and an unrealistic need for control (Eum and Rice, 2011). Maladaptive perfectionists often have extremely high expectations for themselves which go beyond being motivational and end up being detrimental. These people are also more likely to be motivated by fear of failure rather than a drive for success (what psychologists refer to as avoidance goal orientation, see Pychyl, 2009 for more information), a mindset that was found to increase the likelihood of test anxiety. While these negative emotions might not affect you during the immediate test, it can make it very difficult to motivate and prepare for the next one.

Strategies to Reduce Test Anxiety

It’s unrealistic to expect a completely anxiety-free test experience. Tests are inherently stressful situations. They are difficult, time-constrained, and often have major consequences. That being said, there are a number of strategies you can use to reduce test anxiety to manageable levels and maybe even benefit from an anxiety-induced test boost.

Be Prepared

It goes without saying that the best way to avoid excessive stress on test day is to simply be prepared. The more you know the material, the more confident you will feel walking into the test room. A 1995 study by Rocklin and Thompson showed that when presented with a difficult test, students with the lowest levels of anxiety performed best. However, when taking an easy test, moderately test-anxious students outperformed their low-anxious and high-anxious peers. Being well-prepared for a test can make a difficult test feel easy, allowing you to benefit from moderate anxiety levels.

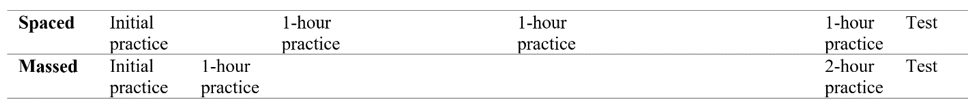

Begin preparing early and space out different topics over the duration of preparation rather than studying the same material all at the same time. A 2012 study by Roediger and Pyc found that students who studied 10 minutes per day for 3 consecutive days (spaced studying) performed no different than students who studied for 30 minutes on a single day (massed studying)when tested one day after. However, when tested a week later, the spaced group greatly outperformed the massed group, suggesting that spaced studying is highly beneficial for long-term information retention. Since most final exams are cumulative, spaced studying for the midterm now may save you time re-studying midterm-material later. See Figure 1 for examples of studying schedule during the spaced and massed studying formats.

Figure 1: Sample Spaced vs Massed practice schedule. Space between practice sessions should increase as time progresses.

The same study also found a positive effect for interleaved practice– practicing all different types of problems during the same study session – when compared to blocked practice– practicing only one type of problem during each study session. Even though the interleaved training group performed worse when tested one day later, they performed nearly twice as well as the blocked group on the one-week-later test. By using both interleaved practice and spaced studying techniques, you can greatly improve long-term retention of material and ultimately feel much more prepared come test day.

In addition to a more spaced-out and organized study schedule, self-testing is a great way to ensure that you know the material. People often don’t realize gaps in their knowledge until the first time they are forced to recall it without help. Testing yourself on material early and often can reveal these gaps and prevent anxiety-inducing surprises on the day of the test.

Desensitization Training

Preparation doesn’t have to stop at just knowing the material. Preparing for the actual test environment by practicing under realistic conditions (a process known as desensitization training) can be especially helpful in reducing many physiological symptoms of test anxiety (Allen, 1971). The techniques of desensitization training are based on the principles of exposure therapy, which involves exposing patients to their source of anxiety in a controlled situation and is often used to treat PTSD or obsessive-compulsive disorder. Preparing in advance for the stresses of a real exam environment can greatly reduce anxiety levels. This can be done by physically studying in the test room, completing practice tests under realistic conditions, or simply visualizing the test environment and imagining some of the emotions and reactions you expect to feel. Studies have shown desensitization training to be especially beneficial for high test-anxious students dealing with information retrieval problems by reducing the interfering thoughts created by an unfamiliar environment (Naveh-Benjamin, 1991).

Prime Competency

Even if you don’t feel particularly well-prepared for the test, there are steps you can take to temporarily heighten your own perception of competence via priming (Lang and Lang, 2010). Reminding yourself of previous successful tests right before an exam can give you the illusion of being more prepared than you might actually be. While this won’t make up for not knowing material, it can alleviate many of the more distracting symptoms of test anxiety. Often times, test-anxious students using this strategy find that they are not actually as underprepared as they believed (Lang and Lang, 2010).

Reframe Anxiety as Excitement

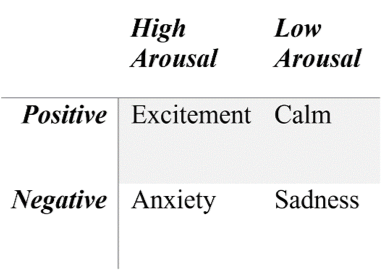

Table 1: Emotional Valence × Arousal Level

Most people’s first instinct when facing anxiety is to take a few deep breaths and try to calm down. However, trying to shift from feeling anxious (a negative, high-arousal state) to feeling calm (a positive, low-arousal state) is deceptively difficult to do (Brooks, 2014). Attempting to suppress only the physiological symptoms of severe test anxiety is actually such a psychologically strenuous process that it could end up limiting test performance even more (Coté and Miners, 2005). Furthermore, shifting to a calm state will prevent you from taking advantage of the increased alertness associated with high-arousal.

Table 1 illustrates the relationship between arousal level and emotional valence, a measure of how intrinsically pleasant it is to experience the emotion. Anxiety and excitement are said to bearousal congruent, meaning they appear very similar from a physiological perspective but differ in whether they are perceived as positive or negative. Because of this similarity, reappraising anxiety as excitement is much less taxing and much more effective than trying to change your level of arousal (Gross and Levenson, 1993). It’s very easy to underestimate how much control our physiological state has over our emotions. Simply telling yourself that you are excited for the test rather than stressed or anxious can reduce many of the negative cognitive effects of test anxiety while maintaining the heightened alertness brought on by your state of high physiological arousal (Kondo, 1997).

Avoid Comparing Yourself to Others

Many of the emotional symptoms of test anxiety stem from the belief that everyone else is less nervous and more prepared to take the test than you are. Focusing on others’ appearance relative to yours distracts from your own mental state and results in unwarranted feelings of inferiority. It’s best to avoid any kind of comparison between yourself and your classmates. During last-minute pre-test study sessions, focus only on the material rather than discussing how many more hours your friend spent on test prep than you. During the test, don’t try to deduce your classmates’ performance based on how relaxed they look. Focus on yourself and your test only.

If you find yourself unable to avoid comparisons, you can still help reduce anxiety by acknowledging that your classmates are likely far more nervous than they’re letting on. This at least helps make the comparison more accurate and favorable to you; it’s very difficult to accurately assess another person’s preparedness based only on their appearance.

Take Care of Your Health

Ok, this one’s pretty obvious, but it’s so important that it’s worth mentioning. The benefits of living a healthy lifestyle extend far beyond just dealing with test anxiety. Take care of your physical and mental health by getting enough sleep the night before a test, drinking enough water, not overdoing it with caffeine, and exercising regularly. The anxiety-reducing effects of proper sleep and exercise are widely-accepted and undisputable (Anderson and Shivakumar, 2013; Coe et al., 2016).

Conclusion

Test anxiety may seem like an overwhelming problem to overcome. In reality, it probably isn’t feasible or even beneficial to get rid of test-day nerves entirely. However, learning to manage test anxiety is one of the most valuable skills to have as a student. Learning to reduce test anxiety to a reasonable level can provide a notable boost in academic performance and can even help when dealing with other anxiety-causing situations. As the prevalence of test anxiety continues to increase, it’s surprising that such an influential skill is so deemphasized in academic curriculums. It’s time to take test anxiety seriously. By educating ourselves and working to apply the right strategies, we can make test anxiety a rarity and make test-taking a more positive experience for everyone.

References

Allen, G. J. (1971). Effectiveness of study counseling and desensitization in alleviating test anxiety in college students. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 77(3), 282–289.

Anderson, E., & Shivakumar, G. (2013). Effects of Exercise and Physical Activity on Anxiety. Frontiers in Psychiatry, 4.

Angelidis, A., Solis, E., Lautenbach, F., van der Does, W., & Putman, P. (2019). I’m going to fail! Acute cognitive performance anxiety increases threat-interference and impairs WM performance. PLOS ONE, 14(2), e0210824.

Brooks, A. W. (2014). Get excited: Reappraising pre-performance anxiety as excitement. Journal of Experimental Psychology: General, 143(3), 1144–1158.

Cassady, J. C., & Johnson, R. E. (2002). Cognitive Test Anxiety and Academic Performance. Contemporary Educational Psychology, 27(2), 270–295.

Coe, D. P., Pivarnik, J. M., Womack, C. J., Reeves, M. J., & Malina, R. M. (2006). Effect of Physical Education and Activity Levels on Academic Achievement in Children: Medicine & Science in Sports & Exercise, 38(8), 1515–1519.

Côté, S., & Miners, C. T. H. (2006). Emotional Intelligence, Cognitive Intelligence, and Job Performance. Administrative Science Quarterly, 51(1), 1–28.

Duffy, M. E., Twenge, J. M., & Joiner, T. E. (2019). Trends in Mood and Anxiety Symptoms and Suicide-Related Outcomes Among U.S. Undergraduates, 2007–2018: Evidence From Two National Surveys. Journal of Adolescent Health, 65(5), 590–598.

Eum, K., & Rice, K. G. (2011). Test anxiety, perfectionism, goal orientation, and academic performance. Anxiety, Stress & Coping, 24(2), 167–178.

Gross, J. J., & Levenson, R. W. (1993). Emotional suppression: Physiology, self-report, and expressive behavior. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 64(6), 970–986.

Kavakci, O., Semiz, M., Kartal, A., Dikici, A., & Kugu, N. (2014). Test anxiety prevalance and related variables in the students who are going to take the university entrance examination. Dusunen Adam: The Journal of Psychiatry and Neurological Sciences, 301–307.

Kondo, D. S. (1997). Strategies for coping with test anxiety. Anxiety, Stress & Coping, 10(2), 203–215.

Lang, J. W. B., & Lang, J. (2010). Priming Competence Diminishes the Link Between Cognitive Test Anxiety and Test Performance: Implications for the Interpretation of Test Scores. Psychological Science, 21(6), 811–819.

Naveh-Benjamin, M. (1991). A comparison of training programs intended for different types of test-anxious students: Further support for an information-processing model. Journal of Educational Psychology, 83(1), 134–139.

Piedmont, R. L. (1995). Another look at fear of success, fear of failure, and test anxiety: A motivational analysis using the five-factor model. Sex Roles, 32(3–4), 139–158.

Pychyl, Timothy A. (2009). Approaching Success, Avoiding the Undesired: Does Goal Type Matter? Psychology Today. https://www.psychologytoday.com/us/blog/dont-delay/200902/approaching-success-avoiding-the-undesired-does-goal-type-matter

Rocklin, T., & Thompson, J. M. (1985). Interactive effects of test anxiety, test difficulty, and feedback. Journal of Educational Psychology, 77(3), 368–372.

Roediger, H. L., & Pyc, M. A. (2012). Inexpensive techniques to improve education: Applying cognitive psychology to enhance educational practice. Journal of Applied Research in Memory and Cognition, 1(4), 242–248.

Figure 1: Sample Spaced vs Massed practice schedule. Space between practice sessions should increase as time progresses.

Table 1: Emotional Valence x Arousal Level