“It’s hard to explain how amazing and magical this experience is. First of all, there’s the astounding beauty and diversity of the planet itself, scrolling across your view at what appears to be a smooth, stately pace… I’m happy to report that no amount of prior study or training can fully prepare anybody for the awe and wonder this inspires.” ~Kathryn D, NASA Astronaut (cited in Robinson et al., 2013, p.81)

“If somebody’d said before the flight, ‘Are you going to get carried away looking at the earth from the moon?’ I would have say [sic], ‘No, no way.’ But yet when I first looked back at the Earth, standing on the moon, I cried.” ~Alan Shepard, NASA Astronaut (cited in Nardo, 2014, p. 46)

“From space I saw Earth—indescribably beautiful with the scars of national boundaries gone.” ~Muhammad Ahmad Faris, Syrian Astronaut (cited in Hassard & Weisberg, 1999, p. 1)

Within this frame sits the planet which we call home. This one picture fits every person you have ever met, ever loved, and have ever even heard of, living or dead. All the nations, wars, politics, stories, history, empires, landmarks, songs, works of art, and every other thing you know started here. Lives here.

And in the background, that black backdrop of space, is miles and mile of nothing. We are surrounded by nothingness, protected from solar winds, radiation, and the occasional wandering meteroids by our atmosphere and magnetic fields. Upon this blue marble is a world abundant with life, millions of species, billions of humans and even more animals, insects, and other forms of life. This is our planet, our Earth.

The Overview Effect

When astronauts prepare to go into space for the first time, very few of them expect to spend most of their time looking down at the Earth while the window across the way has a view of the great beyond.

But they do.

Many astronauts have reported when they looked down on the Earth, they experienced radical shifts in consciousness, some of which can feel deeply emotional and promote a sense of connectedness with the Earth and with one another. Termed “the overview effect” by White (1987), he described this effect as “a profound reaction to viewing the earth from outside its atmosphere.” This overview effect has been described by many astronauts as one of the most meaningful moments of their lives.

So why is viewing the Earth from space such a powerful experience for so many astronauts?

The borrowed Japanese word “yugen” gets tossed around by many space-lovers as the deep emotional experience felt when reflecting on the beauty of vastness of the universe. Yet, psychologists believe that this overview effect, or yugen, can be best explained through a heightened feeling of awe.

Silvia, Fayn, Nusbaum, and Beaty (2015) describe awe as a “powerful state,” characterized by “wonder, amazement, fascination, or being moved and touched” (p.376). Research has shown that two things in particular can promote a feeling of awe— aesthetic beauty and a sense of vastness. Nature in particular has been hailed as a great source of awe, as not only are things like trees and flowers aesthetically pleasing to look at, but places like the grand canyon or yosemite can make one feel ever-so-small in comparison.

When we think about the overview effect, viewing Earth from outer space might provide an even greater natural beauty and scaling vastness to transform awe into this “life-changing” state. Yaden et. al (2016) proposed that “the juxtaposition of Earth’s features against the black vacuum of space might be sufficient to emphasize themes both perceptual (beauty, activity, visible signatures of human civilization) and conceptual (vitality, interconnectedness, preciousness)” (p.4). Simply put, seeing our planet in a black sky not only makes it seem even more vibrant and beautiful, but seeing it as a collective whole promotes a feeling of unity and connectedness with the Earth.

In their research on awe, Silvia et al. (2015) showed participants images of the sky, earth, and deep space and asked participants to report if they experienced various aspects of awe (getting chills, feeling fascinated). They found that not only do individuals report feelings of awe when looking at space pictures, but this was significantly predicted by openness to experience (OTE)— a personality trait related to curiosity and appreciation for aesthetics. According to Silvia et al. (2015), OTE affects people’s’ experiences with art and other aesthetics through many different ways. Individuals who are high in OTE value aesthetics more, are more interested in novel and unusual things, and have more knowledge about art and aesthetics.

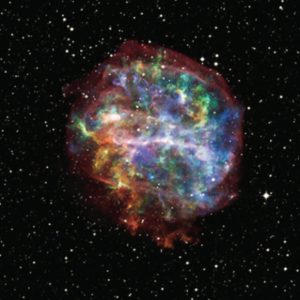

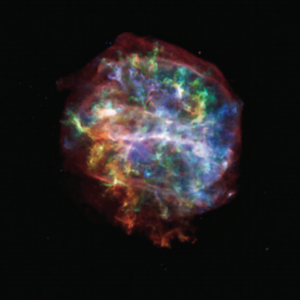

Such knowledge about art and aesthetics might be a key catalyst to achieve the heightened feeling of awe from the overview effect. Some research has shown that knowledge about an image can change our reaction to it. In their study on aesthetics, Smith et al. (2011) asked participants in their study to view a series of space images, and measured how long individuals spent looking at an image. In one part of their study, they presented two versions of the G292-B supernova– one with the stars in the background, and one without. For each of these conditions, one set of images were presented without annotation, while others had the following annotation:

“G292.0+1.8 is a young supernova remnant located in our galaxy. This deep Chandra image shows a spectacularly detailed, rapidly expanding shell of gas that is 36 light years across and contains large amounts of oxygen, neon, magnesium, silicon and sulfur. Astronomers believe that this supernova remnant, one of only three in the Milky Way known to be rich in oxygen, was formed by the collapse and explosion of a massive star. Supernovas are of great interest because they are a primary source of the heavy elements believed to be necessary to form planets and life” (p.211)

Interestingly, the researchers found that there was no difference in looking time between the two versions of the images (stars vs. no stars). However, participants who had the accompanying text that provides information on the image not only looked significantly longer at the image, but rated it as more attractive.

As astronauts are often advanced scientists and engineers, their experiences reflecting on the Earth might be contextually rich (e.g. they may be thinking on the advanced processes in our magnetic field, the structure of the atmospheric layers, our “goldilocks” orbit around the sun). This, combined with the sense of vastness the earth provides orbiting in a black sky, and perhaps some personality traits may all play a role in this effect.

But we don’t really know. Not only are previous astronauts an extremely hard sample to recruit, but one cannot truly experience the overview effect unless they are orbiting the Earth. Of course we can try to pinpoint the mechanisms of awe using images of space here on earth to conduct good research, but when it comes to applying this work to the overview effect, we might only be left to speculate.

As Sam Durrance (NASA Astronaut) said:

“You’ve seen pictures and you’ve heard people talk about it. But nothing can prepare you for what it actually looks like. The Earth is dramatically beautiful when you see it from orbit, more beautiful than any picture you’ve ever seen. It’s an emotional experience because you’re removed from the Earth but at the same time you feel this incredible connection to the Earth like nothing I’d ever felt before” (cited in Redfern, 1996, p. 1).

If you are interested in learning more about the overview effect, check out the 20 minute documentary of the Overview Effect by clicking here!

References

Hassard, J., & Weisberg, J. (1999). Environmental science on the Net: The global thinking project. Parsippany, NY: Good Year Books.

Nardo, D. (2014). The blue marble: How a photograph revealed earth’s fragile beauty. Mankato, MN: Compass Point Books.

Redfern, M. (1996, April 21). Science: A new view of home. Independent. Retrieved from http://www.independent.co.uk/arts-entertainment/science-a-new-view-of-home-1306095.html

Robinson, J. A., Slack, K. J., Olson, V., Trenchard, M. H., Willis, K. J., Baskin, P. J., & Boyd, J. E. (2013). Patterns in crew-initiated photography of earth from the ISS: Is earth observation a salutogenic experience? In D. A. Vakoch (Ed.), On orbit and beyond: Psychological Perspectives on Human Spaceflight (pp. 51–68). Berlin, Germany: Springer-Verlag.

Silvia, P. J., Fayn, K., Nusbaum, E. C., & Beaty, R. E. (2015). Openness to experience and awe in response to nature and music: Personality and profound aesthetic experiences. Psychology of Aesthetics, Creativity, and the Arts, 9(4), 376-384. Retrieved from http://search.proquest.com/docview/1705005844?accountid=14512

Smith, L. F., Jeffrey, K. S., Kimberly, K. A., Randall, K. S., Jay, B., & Kelly, K. (2011). Aesthetics and astronomy: Studying the public’s perception and understanding of imagery from space. Science Communication, 33, 2, 201-238.

White, F. (1987). The overview effect: Space exploration and human evolution. Boston: Houghton Mifflin.

Yaden, D. B., Iwry, J., Slack, K. J., Eichstaedt, J. C., Zhao, Y., Vaillant, G. E., & Newberg, A. B. (2016). The overview effect: Awe and self-transcendent experience in space flight. Psychology of Consciousness: Theory, Research, and Practice, 3, 1, 1-11.