Several months ago, I wrote a post about how online dating has shifted the way people search for and establish romantic relationships in the modern era. Notably absent from that article was any mention of what has become the fastest growing, and arguably the most popular, dating app of the past several years: Tinder. Why didn’t Tinder make it into my discussion of the potential benefits and drawbacks of online dating? To put it simply, Tinder seems to fall into a league of its own. To categorize it as a dating app in the same genre as websites like Match or OkCupid may be entirely missing the mark as to why exactly Tinder has become so popular. Most users sign up for dating sites like Match, for example, with intentions of finding a romantic partner, whether it be short or long-term. In contrast, Tinder has earned a reputation as more of a ‘hook-up’ (and sometimes even purely entertainment) app, where users make decisions based on first impressions of physical appearance and carry relatively low expectations regarding romantic outcomes.

Before I get any further, let’s address the Tinder basics for readers less familiar with the app. Tinder is a mobile dating application that was first launched in 2012. Users sign up through Facebook, and Tinder profiles are limited to providing an individual’s age, first name, photos, and (sometimes) an abbreviated personal blurb. Tinder also identifies a user’s current location in order to offer him/her potential ‘matches’ within the same geographical region, allowing the app to be used on-the-go. For every potential match that shows up on the screen, you have a simple decision: swipe right (to ‘like’) or left (to say ‘no thanks’). If two users mutually “like” each other, they are connected through a chat window, where they can now begin an exchange.

It is estimated that up to 50 million people use Tinder every month, and there are more than one billion swipes per day. Despite the high number of swipes, only about 12% of these result in matches on a daily basis . And, more recently Tinder has implemented modified restrictions on the number of “likes” a user can give out per day (unless you’d like to pay $9.99 per month for an unlimited supply), but that’s an entirely different story. Based on the numbers alone, it’s fair to conclude that Tinder is an extremely popular app, particularly among young singles. But, what are people saying about it? To get a sense of some common sentiments related to Tinder, I asked a not-so-random sample of 21-33 year olds to describe this app to me in one sentence. Here are some of the responses:

Tinder is….

“An app young people use to aid in hooking up”

“The closest online dating has come to replicating meeting someone in real life, but ultimately a soulless experience”

“The unfortunate reality of being 25”

“A fun way to waste time with people you’d never want to date in real life”

“Full of creepy men”

“Superficial online dating”

“A next gen ‘Hot or Not’, hookup and ego boost app”

“A hot, sometimes successful, mess”

“A scroll through of endless [jerks] to lead you to hate yourself”

“The manifestation of our cultural obsession with appearance and attention deficits”

And some other thoughts:

“I still swipe right sometimes and I’ve been in a relationship for over two years”

“It started out as a hook-up app that has transformed into a dating app. People are taking it more seriously now. [But] if you don’t respond fast enough, [your matches] quickly move on.”

“Nothing’s worse than Tinder.”

The majority of people quoted above are past or current Tinder users. There’s an entire Instagram account dedicated to collecting the ridiculous, inappropriate, and sometimes just downright bizarre exchanges that take place on Tinder (see image on left). So, how do we reconcile the fact that the most popular dating app in the country seems to be the subject of so much criticism, even from its own users? Of course, there is not a clear-cut answer to this question. But here, with a little help from psychological theory (this is a psychology blog, after all), I’ll attempt to shed some light on why Tinder has become such a cultural phenomenon.

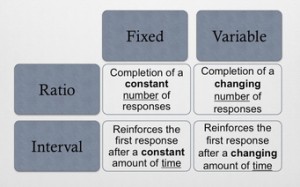

Operant Conditioning & Schedules of Reinforcement

Let’s rewind nearly 75 years to the research of B.F. Skinner, arguably one of America’s most influential behavioral scientists. Skinner studied operant conditioning, seeking to understand how different forms of reinforcement in our environments affect our future behavior. When a behavior, let’s say putting a coin in a slot machine, is followed by some form of positive reinforcement (i.e., winning money), there is an increased probability that we repeat this behavior in the future. Sure, this sounds obvious to us now, but Skinner’s behaviorist theories emerged at a time when psychological research centered around understanding human consciousness through forms of introspection (think, Freud). As such, Skinner’s emphasis on analyzing observable behaviors revolutionized the field of psychology. Of particular relevance to the current topic, Skinner also identified the specific conditions under which reinforcement would create the highest and most consistent rates of desired behavioral responses, which he termed ‘schedules of reinforcement’. Are we more likely to keep gambling if we never win, always win, or something in between? The answer seems to fall somewhere in the middle—Skinner termed ‘variable ratio’ schedule to describe a reinforcement pattern whereby a specific proportion of responses will be rewarded (the ‘ratio’ component), but the pattern/order of reinforcement is not fixed (the ‘variable’ part). It is precisely this tactic that can account for casinos’ success—gamblers always have the possibility that ‘this next coin will win’, but the pattern is unpredictable and the likelihood of winning consistently low.

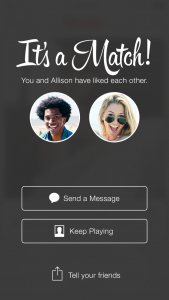

Still wondering how this relates to Tinder? Let’s replace the coin with a swipe (and a ‘like’ swipe in particular) and replace the big money reward at the slot machine with those magic words, “It’s a match!”. That is, each time we swipe right (like) for another user, there is a possibility that they have also liked us. Sometimes it may take two right swipes before a match, other times, 20. But just like those slot machines, the anticipation of an eventual match combined with the unpredictability of reinforcement may fuel the continued swiping. In this sense, one could argue that Tinder, at its core, is driven by Skinner’s principles of operant conditioning. To maintain its success, Tinder wants to encourage users to swipe, and this behavior is maintained by periodic rewards in the form of matches.

Of course, this is assuming you buy into the idea that a Tinder match is truly rewarding. One set of findings that supports this suggestion comes from studies showing that when someone ‘likes’ our Facebook status or retweets our Twitter post, we experience an increase in dopamine (a neurotransmitter associated with reward/pleasure) in the brain reward centers. These simple instances of positive reinforcement online can actually activate reward centers, which in turn makes the behavior more desirable to us in the future. Although we know essentially nothing about the effects of Tinder at a neural level, much like Facebook likes, matching may offer users unpredictable, yet satisfying glimpses of social approval and validation, which in turn encourages future swiping.

Low Investment, Low Stakes

Okay, so what happens after a match? Sometimes, nothing. But when an exchange is initiated, conversations typically mirror texting, with short, back-and-forth messages (i.e., the modern equivalent to AIM’s ‘hey, sup’; ‘nm, u?’). Herein lies another selling point of Tinder—conversations require very little effort. Whereas users on full-profile websites like OkCupid may feel pressure to craft a relatively substantive, charming first message based on the information provided by someone’s detailed profile, Tinder profiles convey little to no background about a user. As such, sending a simple “Hey, what’s up” in Tinder-land may be viewed as a natural starting point for an exchange—after all, what else is someone supposed to say? Similarly, responding to a message on Tinder requires minimal effort, and represents less of an investment than crafting a comprehensive, witty reply to that OkCupid message. These differential levels of upfront effort and investment have an important impact on users’ subsequent expectations and their emotional reactions when expectations are not met. For example, research from behavioral economics indicates that humans experience the greatest disappointment when a given outcome turns out worse than expected—that is, disappointment can be thought of as proportional to the difference between our expectations and reality. How do we avoid disappointment? One option is to shift an outcome to line up with our expectations, but this is typically difficult and/or impossible (i.e., outcomes are usually out of our control). The alternative option involves avoiding disappointment by strategically lowering one’s expectations about a desired outcome.

In the world of online dating, Tinder may represent the embodiment of lowered expectations. You’ll note that none of the quotes mentioned at the beginning of the article talk about Tinder as “a promising way to find a romantic partner.” As such, Tinder’s greatest weakness may also be its strength. The effortless swiping, the mindless messaging—these features set users up to expect very little from the app, thus limiting opportunities for disappointment.

Entertainment Value

Thus far I’ve attempted to situate users’ love/hate relationship with Tinder within literature from various psychological domains. There are potential behavioristic explanations for our somewhat addictive swiping patterns (i.e., unpredictable reinforcement), and theory from behavioral economics sheds light on how Tinder might limit the gap between our expectations and reality, minimizing opportunities for disappointment. But, it’s important to note that Tinder’s popularity may also boil down to something much more simple—it’s entertaining. As busy as our lives may seem at times, most people experience boredom on a fairly regular basis, whether it’s while standing in line at the grocery store, completing a mind-numbing task at work, or sitting at your airport gate an hour before boarding. Boredom has more technically been defined as “an aversive state of wanting, but being unable, to engage in satisfying activity”—and as with any other aversive state, our goal is to remove the discomfort. So long as their phones are handy, Tinder is (literally) in the palm of users’ hands at all hours of the day. Whether there’s time for two swipes or two hundred, the app offers on-the-go entertainment, even (and perhaps especially) for users with no intention of meeting or talking to other users (e.g., our swiping respondent in the two-year relationship). Even Tinder seems to acknowledge that it functions much like any other game on your phone–when you match with a user, it offers you the option to send the person a message or “keep playing” (i.e., swiping).

Love it or Hate it

Many of Tinder’s draws are also its drawbacks—it frequently offers temporary entertainment by encouraging somewhat mindless, superficial mate selection. But, we also must remember that these sorts of judgments are not something new. As one of my respondents astutely noted, “Tinder has become closest online dating has come to replicating meeting someone in real life.” That is, determining compatibility and judging others based on physical appearances isn’t unique to Tinder—these are the same factors that can often influence whether we approach a random stranger in ‘real life’. Similarly, first exchanges in person typically line up much more closely with the Tinder way of things; it’s rare we approach a stranger at a bar and craft an extended speech to convey our interest, a la OKCupid (moreover, we typically have no background information to begin with). So, it’s not that Tinder is necessarily unique in the underlying processes that guide users’ interactions. Rather, Tinder’s popularity, and what may make it more desirable than seeking out others in the ‘old-fashioned way’, centers around its constant accessibility, offering opportunities for entertainment and (potentially) a mini ego boost at your fingertips.