“O Captain! my Captain! our fearful trip is done,

The ship has weather’d every rack, the prize we sought is won,

The port is near, the bells I hear, the people all exulting,

While follow eyes the steady keel, the vessel grim and daring;

But O heart! heart! heart!

O the bleeding drops of red,

Where on the deck my Captain lies,

Fallen cold and dead.”

– Walt Whitman, from

O Captain! My Captain!

By now you must have heard the news, and like most of you, Robin Williams’s death caught me by surprise, and filled me with a mix of emotions that included shock, dread, sadness and sympathy. Despite a life full of accolades, humor, and an unending list of heartwarming, inspiring roles and quotes, it was a little known fact that Williams suffered from major depression, and in 2014, had admitted himself for sobriety treatment for alcoholism. Although unconfirmed, evidence points to his death being caused by self-inflicted asphyxiation. If you are like most people, you’re probably concerned with the question of “why”. Why do people die by suicide?

Rapid reactions around the web:

Suicide is Cowardly

“…yet, something inside you is so horrible or you’re such a coward or whatever the reason that you decide that you have to end it. Robin Williams, at 63, did that today.”

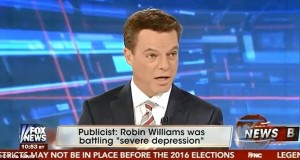

Fox News anchor Shephard Smith, in a rather unclassy move, connotes that a part of the reason for Williams’s death may have been his cowardice. He has since apologized for the comment.

Suicide is Selfish

http://www.tmz.com/2014/08/11/robin-williams-suicide-dead-todd-bridges-twitter-selfish/

Diff’rent Strokes television star Todd Bridges, who plays the character “Willis”, also had a few choice words to say about Williams’s alleged actions, commenting on Twitter that it was a “very selfish act”. Like Smith, he has quickly apologized for his comments.

While these positions are wholly subjective and have no place in scholarly discourse, they reflect how little we know about relevant academic questions on the nature of emotion, self-destruction, and death. These questions have eluded philosophers and scholars for millennia.

So far, here’s what we think we know:

The Interpersonal Theory of Suicide

Dr. Thomas Joiner, Robert O. Lawton Distinguished Professor of Psychology at the Florida State University, is one of the leading researchers in suicide. In his 2005 book titled “Why People Die by Suicide”, he proposed what is now known as the interpersonal theory of suicide. In Joiner’s model, people arrive at a suicide attempt through the union of three factors: perceived burdensomeness, lack of belongingness, and a capacity for self-harm.

This model posits that suicidal ideation occurs when one feels like their very existence is a burden to others (perceived burdensomeness), and/or when they no longer feel like they occupy a meaningful place in their social network (lack of belongingness).

A suicide attempt, as Joiner explains, comes when one, in addition to the aforementioned states, acquires a capacity for self-harm. For example, if someone works with guns and later develops a desire to end their life, their familiarity with guns would facilitate their ability to inflict lethal self-harm. The same goes for someone who cuts. While for most of us view cutting as a painful and thus frightening behavior to engage in, if someone has already overcome that fear through repeated cutting, little stands in their way from acting on their suicidal ideation (Not all who cut do so because they are suicidal. For a more in depth discussion of non-suicidal self-injury (NSSI), see Nock & Favazza, 2009). In some ways, our fear of pain and death may be our last line of defense against suicide.

What this implies, according to this model, is that at some point Williams must have felt that either his continued living was burdensome to significant loved ones, or that he no longer felt socially connected, or both. Furthermore, he must have developed an ability to overcome the natural instinct of self-preservation through asphyxiation. Perhaps he had attempted to choke or hang himself before (prior attempt is the strongest predictor of future attempt) and such practice had reduced his fear of asphyxiation. But who did he feel burdensome toward? Who did he feel isolated from? What was it that he lived for and lost? The answers to these questions may never be known.

Next steps for suicide research

Suicide is a pervasive problem from a public health standpoint. It ranks consistently as the 10th leading cause of death, (and has seen an increase in the last couple of years). Suicide is responsible for roughly twice as many mortalities as homicide. Think about what this means – you are twice as likely to die by your own hand than by anybody else. Suicide also presents itself as a particularly difficult research problem whereby many of our tools for conducting psychological research are rendered useless or handicapped. You cannot recruit participants or ask questions to individuals who are dead. Moreover, completed suicide is a behavior with extremely low base-rates, meaning that individuals suffering from major depression, self-harmers, and suicide attempters are likely different people relative to suicide completers. While suicide has been a relevant human phenomenon since the beginning of history, to our knowledge there is limited evidence of naturally occurring suicide occurring in non-humans. This makes animal models of suicidal ideation and behavior generally unavailable. Finally, ethical considerations make the construct of suicide a very sensitive one. A study or study paradigm that would manipulate the degree to which a participant feels suicidal seems indefensible. Those hurdles being said, it is up to psychologists across multiple disciplines to be creative in generating suicide-relevant questions that indirectly address concerns relating to the genesis of suicidal phenomena, some of which are outlined below:

Social Psychology: What kind of broad social constructs lead to mediating psychologies that explain suicide? In other words, what kind of values are held by the broader society that may lead an individual to have a lowered sense of self-worth, high degree of hopelessness, and experience greater amounts of shame?

Affective and Cognitive Psychology and Neuroscience: How do suicidal psychologies (ideation, commitment, attempt, and behavior) come to be? In other words, what kind of changes occur on a structural or chemical level that are responsible for the formation of these psychologies? What kind of cognitive biases might lead to the formation of these psychologies? What endophenotypes predispose an individual to value death over life?

Clinical Psychology: How do we predict and detect when someone is about to act on their suicidal action? When we do, how do we appropriately intervene, and shake an individual off the course of continued self-destructive behavior?

How do we help?

Despite the dearth of answers in the area of scientific knowledge on suicide, over the years, effective interventions have been created.

Dialectical behavioral therapy (DBT) is based on the theory that an individual turns to suicide when he or she believes there is no other way to cope with their distress. DBT works to help the client by arming them with four types of skills: mindfulness, distress tolerance, emotion regulation, and interpersonal effectiveness.

Cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) systematically works on one’s maladaptive thoughts and behaviors to help reduce psychological pain and suffering.

Psychodynamic therapy, an insight-oriented intervention where one processes their emotions and learn how your past experiences relate to one’s current struggles.

Acceptance and commitment therapy (ACT), where one learns to live and commit to a life in line with one’s values.

If you or someone you love has been experiencing suicidal thoughts, please call the National Suicide Hotline at 1-800-273-8255 or go to your nearest emergency room.

If you are interested in either psychotherapy or medication for mental illness, schedule an appointment with a psychologist or psychiatrist (medication) to provide you with treatment options. UCLA students have access to Counseling and Psychological Services (CAPS) located in Wooden West, or at (310) 825-0768.

Otherwise, the following links can help connect you to help.

American Psychological Association Psychologist Locator

Psychology Today Find a Therapist

http://therapists.psychologytoday.com/rms/

Psychology Today Find a Psychiatrist

http://psychiatrists.psychologytoday.com/rms/

If you or someone you love is suffering from suicidal ideation, there is help and we urge you to reach for it.

This post is co-written by Michael Sun and guest writer Jordan Coello, M.A., both authors contributed equally.

—

References

Linehan, M. M., Comtois, K. A., Murray, A. M., Brown, M. Z., Gallop, R. J., Heard, H. L., … & Lindenboim, N. (2006). Two-year randomized controlled trial and follow-up of dialectical behavior therapy vs therapy by experts for suicidal behaviors and borderline personality disorder. Archives of general psychiatry, 63(7), 757-766.

Joiner, T.E. (2005). Why people die by suicide. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Nock, M. K., Joiner Jr, T. E., Gordon, K. H., Lloyd-Richardson, E., & Prinstein, M. J. (2006). Non-suicidal self-injury among adolescents: Diagnostic correlates and relation to suicide attempts. Psychiatry research, 144(1), 65-72.

Nock, M. K., & Favazza, A. (2009). Non-suicidal self-injury: Definition and classification. In M. K. Nock (Ed.), Understanding non-suicidal self-injury: Origins, assessment, and treatment (pp. 9-18). Washington, DC: American Psychological Association.