Every so often, a high profile person claims to suffer from “sex addiction.” Usually it is a Hollywood star, a professional athlete, or an alleged criminal. Typically this is followed by a media blitz dominated by interviews with self-proclaimed experts who weigh in on the legitimacy of this diagnosis. No matter how compelling their arguments are, attempts to legitimize “sex addiction” as bona fide psychopathology are most often met with dismissive eye rolls at best and sheer outrage at worst. This widespread dismissal is at odds with a growing body of research that highlights the severe psychological distress and role impairment that often accompanies such excessive sexual behaviors. Surprisingly, however, the most compelling argument I have seen in favor of the legitimacy of “sex addiction” as psychopathology did not come from a peer-reviewed empirical article but from an independent film released last year.

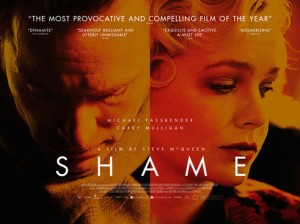

Shame is the second feature film of British director Steve McQueen (not to be confused with the Hollywood movie star of the 1960s and 1970s). The film is a bleak, unflinching portrayal of sex addiction. The film initially won praise for its titillating NC-17 rating and the lead performance of rising star Michael Fassbender, who ignited a media firestorm his willingness to bear it all physically. Although he is an extremely attractive man and the film is full of explicit sex, neither his performance nor the film is remotely sexy. The film is bleak, emotionally raw, and difficult to watch.

Fassbender plays Brandon, a successful Manhattan advertising executive with a secret sexual compulsion. He moves robotically from one sexual release to another, whether it is a threesome with two prostitutes, sex with a stranger in an alley, or masturbation at work. He devotes almost all of his time to seeking sexual encounters, engaging in sexual encounters, and hiding the evidence of his sexual encounters. For Brandon, the cost of these behaviors is high. He has no close relationships of any kind. His primary non-sexual human contact is with coworkers who either idolize his sexual conquests or are the victims of his endless deceits. When he attempts to take a woman out on a date and get to know her prior to having sex with her, the results are crushingly awkward. However, the true depth of Brandon’s self-imposed isolation is not fully realized until the arrival of his younger sister, Sissy. Carrie Mulligan (the Oscar-nominated star of 2009’s An Education and 2011’s Drive) is a fine actress who gives a painfully raw performance as someone equally affected by psychopathology, albeit a different kind. Hers has a more histrionic flair. She is more overt about her insecurity and impulsivity than her brother and makes little attempt to contain the havoc she wreaks. She is never explicitly labeled with a diagnosis, but Sissy appears to be suffering from Borderline Personality Disorder. However, the film is never interested in exploring her too deeply and instead uses her as a way to structure the narrative of the film and as a vehicle for insight into the character of Brandon.

One of the most interesting aspects of the film is its title. Although the film makes it abundantly clear that Brandon’s behavior has reduced his life to an obsessive and unfulfilling hunt for sexual gratification, it gleans most of its effect from the distance at which it keeps the protagonist from the viewer. We see a man disconnected from the world and lacking in any positive affect, but we do not necessarily see a man full of the titular emotion, which is defined as “the painful feeling arising form the consciousness of having done something dishonorable or improper.” The film never explicitly tells the viewer how Brandon feels about his behavior, but it does give a glimpse into his inner world at three pivotal moments. In one, Sissy sings a haunting, slowed down version of “New York, New York” at a swanky jazz club, which drives her brother to tears. Similarly, in the film’s final sequence, Brandon takes a break from running in the crisp early morning and collapses into a sea of tears. And in one of the rare moments they are speaking calmly to one another, Sissy reminds her brother that they are not bad people, they just “come from a bad place.” What is this bad place from which they came? What is the reason for Brandon’s tears? McQueen and Abi Morgan’s enigmatic screenplay refuses to give us clear and simple answers. This decision was infuriating for some, but for me was a bold and realistic depiction of the complex and often unknown etiology of severe psychopathology.

In addition to the question of what caused Brandon and Sissy’s emotional suffering, a question one might be left with after the credits roll is whether Brandon is a type of client routinely seen in clinical settings or a fascinating anomaly concocted by creative screenwriters. The clinical psychology literature suggests the former. A 2010 literature review by Martin Kafka provides a comprehensive discussion of what is known about hypersexuality (the more neutral, behavioral term by which so-called ‘sex addiction’ is referred to in the clinical literature). Although hypersexuality has not been subjected to even a fraction of the rigorous empirical investigation that has gone into the study of other harmful and excessive behaviors (e.g., substance abuse), studies have shown that it is associated with profoundly negative consequences. These consequences are intrapersonal (e.g., anxiety, depression), interpersonal (e.g., harm to intimate relationships, failure to follow through on obligations), and medical (e.g., contraction of HIV). Hypersexuality tends to begin in adolescence, is five times more common in men than women, and is often (but not always) seen as distressing to the affected individual.

There has been much debate in the literature about how hypersexuality should be conceptualized. The term ‘sex addiction’ was popularized by researchers who argued that when engaged in excessively, sexual behavior could result in an addiction-like behavioral syndrome characterized by the use of sex to manage negative emotions, an escalation of sexual behaviors, a subjective “loss of control,” adverse psychological and social consequences, and a withdrawal state during periods of abstinence. The similarly common term ‘sexual compulsion’ arose from the camp that argued that hypersexual behaviors are repetitive behaviors aimed at reducing negative emotional states akin to the compulsions seen in obsessive-compulsive disorder. Some have argued that hypersexuality is primarily a marker of increased sexual desire and the distress associated with managing the increased frequency and intensity of sexual behavior. Others have argued that hypersexuality is similar to many other behavioral syndromes (e.g., kleptomania) in that it is driven by an inability to control impulses.

Kafka’s conclusion is that hypersexuality is best defined as an “increased or disinhibited expression of sexual arousal and desire in association with a dimension of impulsivity.” He argues for its inclusion in the fifth edition of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual for Mental Disorders (DSM-5) and proposes clear criteria to aid clinicians and researchers in diagnosis. Upon hearing this, many will undoubtedly cringe at the idea of pathologizing what appears to be a normal variation in the expression of human sexuality. However, it is important to consider the fact that while hypersexuality is likely to be briefly mentioned as little more than a footnote, 16 disorders related to dysfunctional sexual desires and behaviors will be included in the main text of DSM-5, many of which are less distressing, impairing, and prevalent than hypersexuality. If the expert consensus is that low sexual desire is pathological (as in the case of Hypoactive Sexual Desire Disorder), it seems likely that the opposite end of the continuum may also be pathological.

Why is it that despite a growing body of research suggesting that it is a highly impairing condition, there is a resistance for not only the public but also the mental health community to accept hypersexuality as a legitimate form of psychopathology? One issue is likely that of measurement. How does one define the amount of sex that is pathological? Whereas many can agree on what constitutes the absence of sexual desire, it is much harder to reach a consensus on what is “too much.” Unlike the use of illicit substances, sexuality is a biologically essential behavior and one that is expressed in a wide variety of ways. There is a similar quandary regarding how to decide when other biological drives, such as eating and sleeping, become excessive to the point of pathology. However, as obesity rates sky rocket in this country few would argue with the assertion that there is significant distress and impairment associated with excessive eating. Just because we do not know exactly where to draw the line does not mean there is not a point at which pathology is in fact occurring.

The second barrier to the acceptability of hypersexuality as psychopathology is a moral one. Despite the many ways in which the United States is a liberal and progressive society, we remain remarkably conservative about sex. If in doubt, one needs only to look at the media firestorm caused by the recent Sandra Fluke-Rush Limbaugh controversy (in which a Georgetown medical student was branded a “slut” and a “prostitute” by the conservative talk show host after she spoke before the House Oversight and Budget Reform Committee about what she perceived as unfair policies that blocked her access to birth control). Sex is seen by many as a behavior that can and should be strictly regulated by an individual at all times and in accordance within a certain moralistic framework. Perhaps one’s sex drive can be controlled, but high rates of sexually transmitted infections, unplanned pregnancies, and destructive hypersexual behaviors suggest that such control is difficult for many individuals.

The moral barrier to the legitimacy of hypersexuality as pathology is a troubling one, because the field of clinical psychology should aspire to be free of moral judgments in the absence of clear cases of victimization. Decisions about what constitutes pathology should be determined by the distress and/or impairment experienced by the individual, not whether an individual’s behaviors are in line with a particular moral code. When watching Shame, the question of whether Brandon is responsible for his current state is an independent one from whether or not he is dealing with psychopathology and could benefit from intervention. Perhaps that is why the filmmakers chose not to divulge the origin of Brandon’s hypersexuality. The point is to better understand complex and taboo psychopathology, not to make a moral judgment on it.