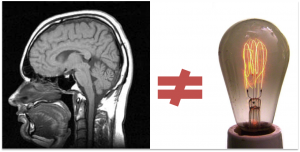

I wrote a post a few months ago about some common misconceptions about functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI), and one of my main points was that the term ‘lights up”, which is often used when describing the areas of the brain that respond to a task, is misleading. Here is what I said on the subject:

First, fMRI does not detect electrical changes in the brain, as ‘lights up’ would imply. Neurons in the brain communicate via electrical and chemical signals; fMRI does not measure either of these. Rather, fMRI measures changes in the amount of oxygenated blood flowing to an area, which is an indirect measure of the metabolic effort needed for neurons to send those electrical and chemical signals. fMRI does not tell us what areas are firing, it tells us what areas are active as a result of firing. Second, the brain is active at all times, doing all sorts of basic cognitive functions, and oxygenated blood is always flowing. While individual neurons might fire on and off, blood flow to areas of the brain do not turn on and off in such a binary fashion, again, as ‘lights up’ implies. With fMRI we attempt to detect what areas are more active for a task (what it is more active than is an important part of fMRI design).

The result of this misleading term is that assumptions are made about what fMRI shows us, and when these assumptions are violated, which is inevitable, the validity of the method is called into question. I have seen both scientist in the field that don’t regularly use fMRI methods and lay people discard fMRI after hearing about studies that highlight aspects of the method that violate the assumptions implied by “lights up”, hence my campaign against this term! Here is a clear example of how using this term can muddle a conversation about fMRI methods:

I recently read a post by Neuroskeptic who was reviewing two very interesting articles about the statistical effects of sampling size and effect size in fMRI research (original articles: here and here). The review and the articles discuss some of the limitations of detecting effects in the brain resulting from current statistical approaches used for fMRI analysis.

In the review the author writes:

Both studies found that pretty much the whole brain “lit up” when people are doing simple tasks. In one case it was seeing videos of people’s faces, in the other it was deciding whether stimuli on the screen were letters or numbers.

With all that data, the authors could detect effects too small to be noticed in most fMRI experiments, and it turned out that pretty much everywhere was activated. The signal was stronger in some areas than others, but it wasn’t limited to particular “blobs”.

So conventional fMRI experiments may just be showing us the tip of the iceberg of brain activity. In a small study, only the strongest activations pass the statistical threshold to show up as blobs, but that doesn’t mean the rest of the brain is inactive. It just means it’s less active. The idea that only small parts of the brain are ‘involved’ in any particular task may be a statistical artefact.

Here we can see the danger of the term “lit up.” The author’s first line, “studies found that pretty much the whole brain “lit up” when people are doing simple tasks”, is highly misleading. If we take “lit up” to mean the brain is awake and firing, then this isn’t news, we know that the brain is always doing stuff, all over the place, all the time (one commenter nice sums it up with: “Are we really surprised that the whole brain is active when we are active?” No, we aren’t).

However, if we take “lit up” to mean that activation during the task is greater then a baseline task, at a set statistical threshold, then this is an interesting finding, but a finding about how we calculate activation, not about the brain. Its not clear what meaning of “lit up” that the author is trying to use (in fact, I’m not sure he knows himself).

Since this distinction is not clear, this leads the author to later points out: ” that doesn’t mean the rest of the brain is inactive. It just means it’s less active.” Again, this isn’t new, research who run fMRI studies know this well. The real interesting findings of these papers isn’t that there are areas that are less active that we didn’t know about; its that with a big enough sample size, we might be able to tease apart some meaning about brain and a task from these less active areas.

The two articles reviewed are rather interesting, and warrant a post on their own, but the review post so nicely illustrated the use of “lights up” I thought I would tackle that first.

The moral of this story is the same as it was for my other post: fMRI does not show us a lightbulb view of the brain, where we see things turning on and off, and we have to be careful not to imply that it does. So tell your friends, stop using the term “lights up”!

Really what I’m talking about is trying to not make this any worse: