I am a big fan of the guys on the Stuff You Should Know podcast. In case you don’t know them, they give 30-45 minute talks on all sorts of interesting topics, from historical, to scientific, to current events. In quite a few of these podcasts they have brought up research that used fMRI (functional magnetic resonance imaging), which they refer to as “the Wonder Machine“, to provide an answer for what parts of the brain are involved with different psychological processes. Now, the Stuff You Should Know guys have some issues with fMRIs, some valid, some less so, but I’m not trying to address those here; I bring them up as an example of a source where the lay person might hear about research using fMRI methods (that, and I like the name “The Wonder Machine”).

Mass media loves to report the more exciting results from these fMRI studies, and readers love hearing about them, however, these reports are often brief and don’t explain exactly how these results were found, or what they actually mean. The interested reader might be curious about how it all works, but find reading the actual scientific paper a bit over their head. There are a lot of places out there where you can look up how MRI/fMRI works (since I mention How Stuff Works before, I’ll link you to their excellent article), so I won’t repeat all that information here, but I thought I would take a swing at addressing a few of the main misconceptions, and questions I have encountered running fMRIs over the last few years. Hopefully this will be helpful for interpreting fMRI results you see in the press.

First, some general questions about MRIs in case you are interesting in participating in a fMRI study, or need to have a clinical MRI scan.

Question: Are MRIs safe? Yes, MRIs are safe. There is no harmful radiation (only a strong magnetic field and radio waves) involved in making an image with a MRI scanner, unlike CAT (uses a good deal of X-rays) or PET (needs a radio-active tracer to form the image) scans. You can have as many MRI scans as you’d like, as far as we know, after about 40 years of using MRIs, there are no long term effects of having an MRI scan. MRIs do pose a danger if you have any ferromagnetic metal in your body.

Misconception:Any metal or implants in your body, dental work, and tattoos mean that you can’t have a MRI. Not true! Well, mostly not true. Like I said above, ferromagnetic metals can pose a danger to a person if they have an MRI scan, but not all metal is ferromagnetic, and many implants are made with non-metal materials and/or non-ferromagnetic metals. Of course, this is not the case for all implants!! DO NOT ASSUME ANY IMPLANT IS SAFE, always tell the MRI tech if you have any implants or metal in your body, and they can look up if it is safe or not. However, having some sort of implant doesn’t guaranty that you can’t have an MRI. The same goes for dental work, a lot of common dental work, filling and crowns, are non-ferromagnetic, but braces and some other implants are. Finally, tattoos are generally MRI safe. Any tattoo done at a reputable parlor should be safe, however, prison tattoos and the like could possibly small bits of metal under the skin, which can pose a risk of heating up painfully in the scanner.

Misconception:MRIs will rip metal out of your body! Again, mostly not true. It take a lot of force to pull something through skin and tissue, and MRIs generally aren’t that strong (MRI strength varies, but for most clinical and research scanners are not the super strong ones). Just because scanners wont pull something out of your body doesn’t mean it can’t hurt you. Metal can heat up in a magnetic field, which can burn; magnetic fields can interfere with electrical systems, which can be very dangerous for devices like pace-makers; even a little bit of motion can be dangerous, if a small piece of metal in the eye that might have come from doing metal work without proper eye protection moves a millimeter it could cut part of the optic nerve. MRIs are strong enough to pull things out of pockets and ones hands, so it is never safe to bring anything metal near a scanner.

Two general facts about MRIs and MRI safety: the magnetic field is not limited to just inside of the machine, and the magnetic field is not turned on and off, it is always on (“the magnate is always on” is the first thing you learn when you MRI safety trained). So when you see doctors on TV shows run into over to MRI scanner with pens, metal clip boards and all sorts of metal objects, those would fly into the scanner, and probably injure or kill the person in the scanner.

Now, on to fMRI!

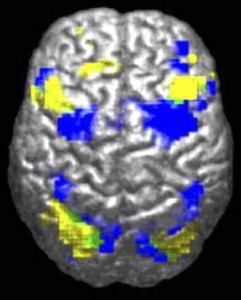

Misconception: fMRI shows what parts of the brain ‘lights up’ when one performs a certain task. While, in some ways this is true, there are a few critical points that make this an inaccurate description. What this really should be is: fMRI shows what parts of the brain are most active when one performs a certain task. This might be a subtle difference, but it points to two important aspects of fMRI research. First, fMRI does not detect electrical changes in the brain, as ‘lights up’ would imply. Neurons in the brain communicate via electrical, and chemical signals, fMRI does not measure either of these. Rather, fMRI measures changes in the amount of oxygenated blood flowing to an area, which is an indirect measure of the metabolic effort needed for neurons to send those electrical and chemical signals. fMRI do not tell us what areas are firing, it tells us what areas are active as a result of firing. Second, the brain is active at all times, doing all sorts of basic cognitive functions, and oxygenated blood is always flowing. While individual neurons might fire on and off, blood flow to areas of the brain do not turn on and off in such a binary fashion, again, as ‘lights up’ implies. With fMRI we attempt to detect what areas are more active for a task (what it is more active than is an important part of fMRI design). As you can tell, I really don’t like the term ‘lights up’ to describe fMRI results.

Misconception: Researchs put people into the scanner and see what areas are active when they perform some interesting task. Like I mention above, fMRI research needs to define what the activation resulting from a task is more active than, aka the control. This makes sense when you think about: if you want to know what part of the brain is active for, say, solving riddles, you would present subjects with written riddles in the scanner. However, when solve a written riddle, you first have to see the words, then process their means, and then finally use some sort of logic or problem solving to get an answer. If all you did was show subjects riddles you would see the parts of the brain that are involved with vision and word processing as well as solving riddles, which doesn’t really tell you about what you want to know. Instead, what researchers do is compare the activation while subjects are performing the task that is being investigating to the activation while the subject is doing a similar task that does not include the aspect of the task that is of interest. In our example, we would find what parts of the brain are more active for solving riddles by comparing the activation for solving written puzzels to the activation for reading similar sentences that are not riddles. This example was fairly simple, often researchers need to be quite creative to find a control for their tasks.

Misconception: Once researchers find the areas of the brain active for a task, they know how the brain performs that task. Not that simple, sadly. The media like to make these type of big statements from single findings. The brain is an extremely complicated thing, and how it performs tasks is equally complicated. All we know from a single fMRI finding is that the active areas are somehow involved with performing that task. Each finding usually generated more questions. This comes down to the heart of research, one finding is only a tiny part of the story, and by collective study and more and more research, more and more parts get put together.

Question: Then what does fMRI research tell us? Basically, fMRI tells us what areas of the brain receive more oxygenated blood in response to one task, as compared to another task. This might not seem like much, but there are lots of ways that this information can be further analyzed to determine what factors effect this activation, and theories and research from previous studies cam tell us what the implications of that activation are. Additionally, tasks can be much more refined that the example I used, and can tell us what part of the brain is involved with very specific parts of mental processes.

Question: All the studies I see that use fMRI have a rather small sample size, isn’t that really bad for statistics? Yes and no, while having more subjects would always help the strength of findings, it is very expensive to do so (it can cost more than a thousand dollars to run an individual subject) , and is not always necessary. Sample size does not always mean number of subjects, it can mean number of measurements. fMRI collects measures of activation from all over the brain, so the sample size is much larger than the number of subjects. Additionally, there is much less variability between subjects’ brain activity than between behaviors, fewer confounding variables. There is a lot of debate on this topic, so all of this can be questioned.

Question: Is fMRI analysis mind-reading? Not really, but maybe soon! fMRI has generally been used to detect what parts of the brain are most active for a task, a task that we know the subject is doing. Given raw fMRI data, you can’t really say much about what that brain might have been doing. There are some exciting new methods of fMRI design and analysis that can reconstruct what a subject is viewing from their fMRI scans. This method could open whole new realms of information about how the brain works. I might cover this type of fMRI in a later blog post here, stay tuned.

Final question: Is fMRI really “the Wonder Machine”? I make a few points here that indicate that fMRI is not as awesome as it is sometimes made out, but that doesn’t mean I don’t think they aren’t incredibly awesome. fMRI is a safe, non-invasive way to peer into the inner workings of the brain, a truly wondrous thing. However, I think its important to not attribute more to fMRI results than is justified. Still, fMRI really is the wonder machine.