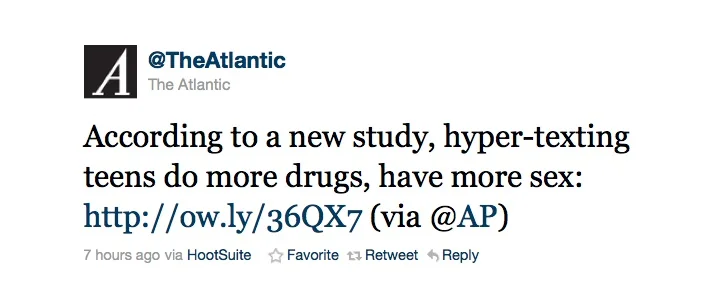

As I spent a few minutes this morning updating my Twitter, I was alarmed to see a post that a friend of mine had retweeted from The Atlantic:

What’s that? Texting no longer only represents a way for teens to ignore their parents at the dinner table and run up the phone bill, it now leads to sex and drugs? The horrors of new technology! Clicking on the link in this tweet leads to a short article on theatlantic.com, with a similar title: “Hyper-texting Teens Have More Sex, Do More Drugs,” (Interesting subtle switch by the way. I wonder which headline inspires more horrified reactions from parents.)

What’s that? Texting no longer only represents a way for teens to ignore their parents at the dinner table and run up the phone bill, it now leads to sex and drugs? The horrors of new technology! Clicking on the link in this tweet leads to a short article on theatlantic.com, with a similar title: “Hyper-texting Teens Have More Sex, Do More Drugs,” (Interesting subtle switch by the way. I wonder which headline inspires more horrified reactions from parents.)

After the explosive title, I was pleased and rather surprised to find that the second sentence of the article presents a very rational follow-up:

“The study, led by Dr. Scott Frank, a professor of epidemiology and biostatistics at Case Western Reserve University, doesn’t suggest that texting leads to sex; it just points out that there is a relationship between the two.”

Despite this important point, I was still upset by the extent to which The Atlantic relied upon sensationalism to draw reader attention. Let’s compare the title of this article with the original article available at the Associated Press. This article is titled “Texting Teens: Sex and Drug Use More Common in Hyper-Texting Teens.” Redundancies aside, I much prefer this title, which acknowledges the correlational, not causal, nature of data. Not all hyper-texting teens are having more sex and doing more drugs, and I am willing to bet that excessive texting isn’t single-handedly causing the trend of risky behavior (Whether or not texts are being used to initiate sexual behavior or organizing drug deals is another question altogether.)

I think the Huffington Post does a fair job of expanding on the headline, especially in this quote:

The study concludes that a significant number of teens are very susceptible to peer pressure and also have permissive or absent parents, said Dr. Scott Frank, the study’s lead author.

“If parents are monitoring their kids’ texting and social networking, they’re probably monitoring other activities as well,” said Frank, an associate professor of epidemiology and biostatistics at Case Western Reserve University School of Medicine.

Nonetheless, by framing the article in terms of texting, the author capitalizes on parents’ fears and misunderstandings when it comes to digital technology. I am willing to guess that this was a fault of the study as well, although I was not in attendance to see it presented. The study doesn’t ask whether or not teens are having MORE sex or abusing MORE drugs now that texting and online social networking are widespread, and it certainly does not test whether technology use is causing deviant behavior. But by focusing on texting, both in the title and throughout the body of the work, the articles online (and again, I assume the original study) highlights texting as being the most important finding, as opposed to just one behavior in a set of associated behaviors.

Let’s take a look at a couple of other headlines:

BBC News- Texting ‘health risk’ for teenagers

Which includes what I can only hope is a misquote:

Dr Frank said: “The startling results of this study suggest that when left unchecked texting and other widely popular methods of staying connected can have dangerous health effects on teenagers.”(emphasis mine)

Since it undoubtedly suggests causality. And one more:

New York Times- Behavior: Too Much Texting is Linked to Other Problems

At the Children’s Digital Media Center @ Los Angeles, our aim is to study the ways that children, teens, and emerging adults (that is, college-age young adults) interact with digital media and the potential implications of this interaction for development. Whether one is approaching new media/technology research from a psychological perspective, an epidemiological perspective, a media studies perspective, or any number of other possibilities, it is important to consider the way that technology factors into greater cultural and social changes. This is especially important in studies like this one, that address such heated topics with very widespread interest. When a study will be translated into a popular article, which will then be translated into a 140 character tweet, almost all of the original context is obliterated. In this case, the original context– parental practices, social interaction among teenagers, other risk factors– is the most important finding of the study. That is a very unfortunate transformation indeed.

A final note: I purposely refrained from commenting on the validity of the idea that teen hyper-texting is dangerous, risky, or developmentally unhealthy; it very well may be all of these things. However, until we have systematically explored that possibility while controlling for other factors, it is inappropriate to imply that texting is psychologically “bad” or leads to other bad behaviors

//