Through the 1950s, smoking cigarettes was seen as stylish and sophisticated in the United States, endorsed by movie stars and doctors alike. By the 1990s, however, the story had completely changed. Smoking was widely viewed as disgusting, inconsiderate, and wrong. What was once a personal choice had turned into a moral issue—a question of right or wrong.

This kind of shift isn’t unique to smoking. In recent years, other health behaviors—like getting vaccinated, wearing masks, and gaining weight—have also become moralized.

My colleagues and I wanted to understand why this happens. Across a series of studies, we found one powerful force behind the moralization of health behaviors: the perception that they cause harm.

Perceived Harm Moralizes Health Behaviors

History offers many examples. The moral backlash against cigarettes grew alongside evidence that secondhand smoke causes lung cancer in children.

A similar argument appears in debates over marijuana use. In 2018, Newark pastor Jethro James opposed legalization, saying he worried about children accidentally consuming THC-infused candy or about young adults losing jobs after failing drug tests. His moral concern stemmed from the belief that marijuana use harms children.

To test the link between perceived harm and seeing a health behavior as a moral issue, we conducted five online studies with more than 2,000 U.S. adults.

In our first study, we created a scale to measure how strongly people believe poor health harms others. Many agreed with statements such as:

- “If I don’t take care of my health, the people in my life suffer.”

- “Unhealthy people bring pain and suffering to those around them.”

People who endorsed these beliefs were also more likely to hold moralized views about health behaviors—seeing actions like smoking, skipping a flu shot, or gaining weight as not just unhealthy, but immoral. In fact, they were more likely to agree with statements like “It is immoral to smoke cigarettes.”

Testing Cause and Effect

To find out whether perceptions of harm actually cause people’s attitudes to become moralized, we ran two experiments.

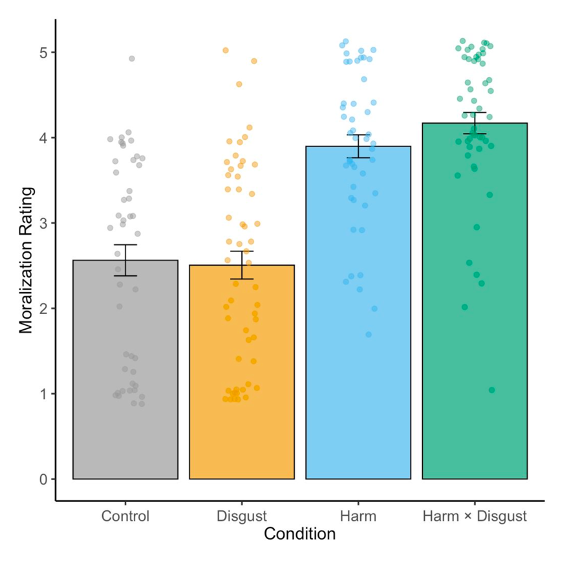

In one, participants read a story about someone attending a public event while sick. We created four versions: the illness was described as either (1) harmful (highly contagious); (2) disgusting but not harmful (symptomatic but not contagious); (3) harmful and disgusting (contagious and symptomatic); or (4) neither harmful nor disgusting (this was our control group).

People judged the behavior as most immoral when the illness was described as harmful. Simply making it “disgusting” wasn’t enough. This shows that harm—not disgust—plays a special role in moralizing health behaviors.

In another study, we tested whether the perception of harm can change a morally neutral health behavior—using sleep aids like melatonin—into a morally charged issue. Participants first rated their moral attitudes about sleep aids, then read information describing sleep aids as either (1) causing harm (increasing traffic deaths from drowsy driving) or (2) preventing harm (reducing traffic deaths by improving sleep).

Both framings led to increases in moralization. Those who read that sleep aids cause harm saw using them as morally wrong. Those who read that they prevent harm saw them as morally praiseworthy.

Why Does This Matter?

Today, many health issues—from vaccination to dieting—have become moral battlegrounds. Understanding why people moralize these behaviors is important because moralized attitudes can lead to conflict with others, stigma, and resistance to positive behavior change.

Our research suggests that that a single psychological factor helps explain the moralization of different behaviors: the perception of harm.

Recognizing this can help people talk to each other more effectively. The next time someone expresses a strong moral opinion about a health issue, it’s worth asking: Who do they think is being harmed?

Our results also offer a note of optimism. When people see a health behavior as preventing harm within their community, they are more likely to view it as morally right. Framing public health actions—like vaccination or staying home when sick—as ways to prevent harm could make them more accepted and valued—and help to promote public health.

For Further Reading:

Pratt, S., Rosenfeld, D. L., Goranson, A., Tomiyama, A. J., Sheeran, P. & Gray, K. (2025). Health behaviors are moralized when perceived to cause harm. Advance Online Publication. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin. https://doi.org/10.1177/01461672251372823

Sam Pratt is a PhD student in Psychology at the University of California, Los Angeles studying morality and consciousness. Follow Sam on X at sampratt99 or on Bluesky at sampratt99.bsky.social.

Note: This post is a forthcoming article in the Society for Personality and Social Psychology’s Character and Context Blog.