Do you have midterms or final exams coming up? We’ll go through a few different types of studying scenarios together to truly answer the question: How can you optimize your study sessions this semester?

Spacing Effect: How often you study matters

1. Studying

You have your exam coming up in a couple of days, and you realize you need to start hitting the books. You spend Monday evening studying until dinnertime, but now what?

2. Waiting for some time

It’s now Tuesday morning. You got some good rest in and you’re ready for the day! However, you realize you signed up for an all-day volunteer shift at the local hospital because you did not consult your class’s syllabus at the beginning of the semester. Are you going to remember what you studied last night during your exam tomorrow?

3. Studying again

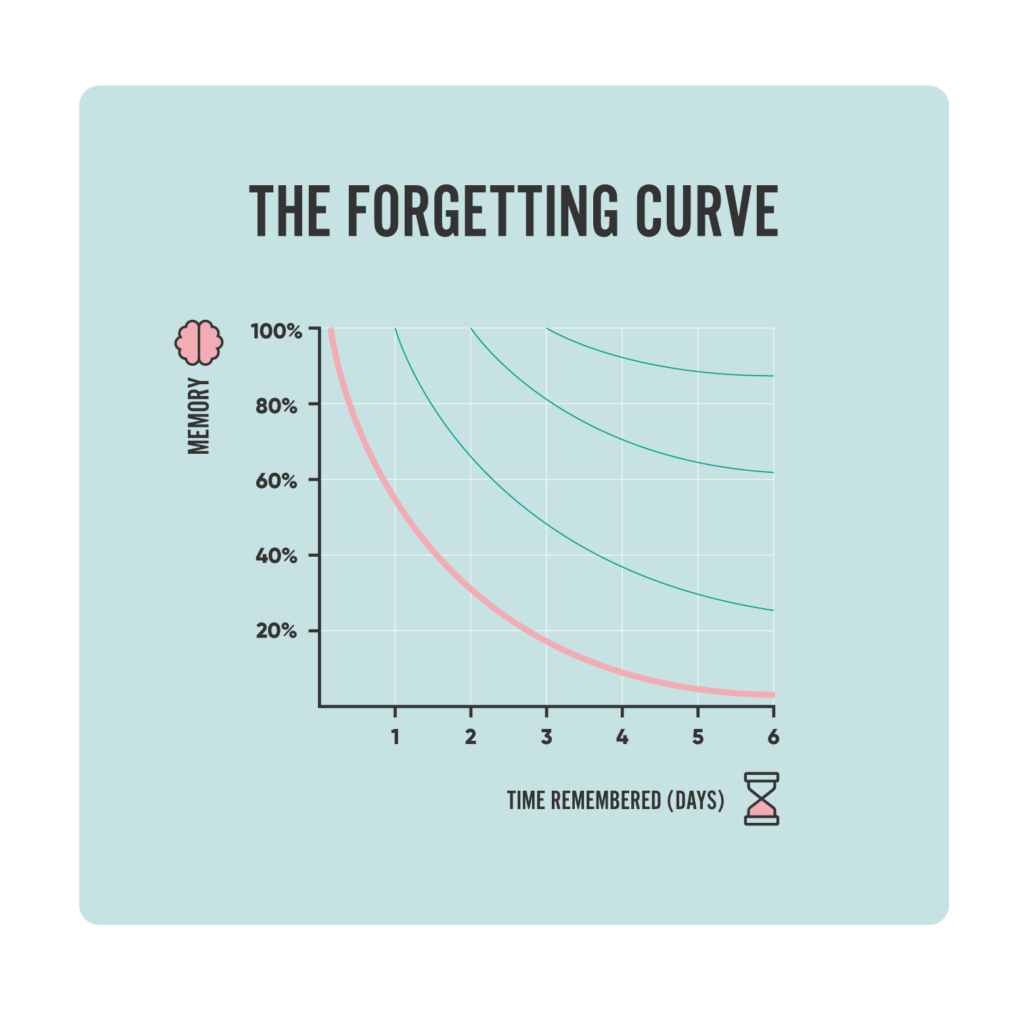

Do not fret, novice student! Psychology research shows that in order to maintain the knowledge you obtained during your prior study session (Monday night), you need to study again. This is what we refer to as spaced repetition learning, or the “spacing effect.” This phenomenon stems from one of the earliest examples of learning and retention research, proposed by Ebbinghaus in 1885. He claimed that information is continuously forgotten over long periods of time; therefore, you constantly need to remind yourself of information to retain it. This is famously known as Ebbinghaus’ Forgetting Curve (Figure 1).

Given this information, you ideally want to study the same information as before, one last time before your exam. You block out a couple of hours on Wednesday morning to get it done before classes, and now you’re golden!

4. Final test

Thursday afternoon comes around, and you’re finally ready for your exam. You had two separate–but identical–study sessions over the past few days, and you know all the answers like second nature! At least, that’s the feeling you have! Now, you wait for your grade.

+ Comparison to studying once

A couple of weeks pass, and you get your exam grades back. You did awesome, given your last-minute studying efforts! However, your friend that was also busy and spent all of Wednesday studying did not do too well. Although disappointing, it is not a surprise. Research shows that spaced repetition allows for better memory of the information compared to learning over a continuous and massed period of time, even when there are manipulations of how much time exists between the study sessions (Carpenter, 2020).

Testing Effect: How to spend time between study sessions

1. Studying

After your prior exam, you want to learn more psychology tricks to optimize your study sessions. You start your studying session a week in advance, but now you’re unsure of how to transition to your break between sessions. Should you go outside for a walk? Start studying for another class? It turns out, you want to do a quick retrieval activity to retain the information you just studied.

2. Retrieval activities

In college, I remember being told to do InQuizitive (mini virtual quiz) activities at the end of every lecture. This was quite annoying to a lot of my classmates, however, there is science to back up this homework assignment. Extensive research shows that immediately recalling the material you have just learned leads to better memory performance. This is called retrieval-based learning, or the “testing effect.” You can achieve this through mini quiz activities (e.g., Kahoot!, Anki, InQuizitive) to make learning a fun and memorable experience for you and your study buddies.

3. Final test

After multiple study sessions where you learn the information and then test yourself afterwards, you are ready for your final test at the end of the week. The greatest part about this method? Your memory for the exam material will be retained from anywhere from a few minutes to even several months afterwards (Carpenter et al., 2009; Larsen et al., 2013; Rowland and DeLosh, 2015; Smith et al., 2013; as cited in Karpicke, 2017).

+ Comparison to learning without retrieval activities

The testing effect is very robust, and countless studies have tried different control conditions to see if the success of retrieval-based learning is due to spending more time on the material. Their joint findings, however, showcase that testing yourself significantly improves long-term memory compared to other study methods.

Pretesting Effect: The study session itself

1. Receive a question or a prompt

Okay. Now you have the ideal study routine, what about the ideal method? You sit down for your first study session of the week and realize you don’t know where to begin. If you were given a study guide by your professor, this is a great place to start.

2. Guess

With whatever knowledge you do have, try to guess the answer to the questions before you look at your lecture slides or notes for the answer. This technique is broadly called “pretesting,” or otherwise known as errorful learning in older literature (for a review, see Metcalfe, 2017).

3. Receive answer

Once you’ve guessed what the answer is to a question, immediately check how correct you were in your notes. Were you correct? Were you wrong? If you were incorrect, that’s even better! Recent work (by myself and colleagues) highlights that depending on what your initial guess was, it either internally bridges the question and answer together in memory or corrects the error originally made to strengthen the question-answer connection (Taggett et al., 2025).

4. Final test

You take the test and you feel more confident in your answer than before! You combined all of the strategies from this article, and now you’re ready to conquer your hardest exams.

+ Comparison to learning without guessing

The earliest and most remarkable finding in the literature is: pretesting with multiple types of questions (i.e., trivia and word-pair associations) led to better memory performance than simply studying these prompts with their answers together (Kornell et al., 2009). Next time you feel inclined to simply read your lecture notes before an exam, think again about how other strategies might benefit you.

So… how do we improve our memory?

These seemingly related branches of psychology research, intuitively, should be combined into the ultimate study technique. Unfortunately, there is no highly-cited research that supports this claim. Future research on overall learning effects needs to be conducted to further assess whether utilizing multiple or all of these techniques can work together to maximize memorization. Until then, pick and choose which of these methods works best for your personal schedule!

References.

Carpenter, S. (2020, April 30). Distributed Practice or Spacing Effect. Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Education. Retrieved 2 Oct. 2025, from https://oxfordre.com/education/view/10.1093/acrefore/9780190264093.001.0001/acrefore-9780190264093-e-859.

Carpenter, S. K, Cepeda, N. J., Rohrer, D., Kang, S. H. K., & Pashler, H. (2012). Using spacing to enhance diverse forms of learning: Review of recent research and implications for instruction. Educational Psychology Review, 24, 369-378.

Ebbinghaus H. (2013). Memory: a contribution to experimental psychology. Annals of neurosciences, 20(4), 155–156. https://doi.org/10.5214/ans.0972.7531.200408

Larsen, D. P., Butler, A. C., Aung, W. Y., Corboy, J. R., Friedman, D. I., & Sperling, M. R. (2015). The effects of test-enhanced learning on long-term retention in AAN annual meeting courses. Neurology, 84(7), 748–754. https://doi.org/10.1212/WNL.0000000000001264

Metcalfe J. (2017). Learning from Errors. Annual review of psychology, 68, 465–489. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-psych-010416-044022

Karpicke, J. D. (2017). Retrieval-based learning: A decade of progress. In J. T. Wixted (Ed.), Cognitive psychology of memory, Vol. 2 of Learning and memory: A comprehensive reference (J. H. Byrne, Series Ed.) (pp. 487-514). Oxford: Academic Press.

Kornell, N., Hays, M. J., & Bjork, R. A. (2009). Unsuccessful retrieval attempts enhance subsequent learning. Journal of experimental psychology. Learning, memory, and cognition, 35(4), 989–998. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0015729

Rowland, C. A., & DeLosh, E. L. (2015). Mnemonic benefits of retrieval practice at short retention intervals. Memory, 23(3), 403–419. https://doi.org/10.1080/09658211.2014.889710

Smith, M. A., & Karpicke, J. D. (2014). Retrieval practice with short-answer, multiple-choice, and hybrid tests. Memory (Hove, England), 22(7), 784–802. https://doi.org/10.1080/09658211.2013.831454

Taggett, J. Z., Ranganath, C., Antony, J. W., & Liu, X. L. (2025). Guess quality moderates how semantic relatedness influences the pretesting effect. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Learning, Memory, and Cognition. Advance online publication. https://doi.org/10.1037/xlm0001543